What is Active Constructive Responding?

How positive we are when our significant other shares with us something they express with enthusiasm and feel strongly about, it turns out, not only speaks volumes about our attachment styles but also, have a long-term impact on the quality and longevity of our relationships.

How positive we are when our significant other shares with us something they express with enthusiasm and feel strongly about, it turns out, not only speaks volumes about our attachment styles but also, have a long-term impact on the quality and longevity of our relationships.

These micro instances are often and easily brushed off as insignificant.

The purpose of this article is to shed light on how what may appear as insignificant is not only in fact extremely meaningful and telling, but also, has a range of implications on the well-being of the relationship and the parties involved.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients build healthy, life-enriching relationships.

This Article Contains:

On Sabotaging the Happiness of Others

This discussion brings us to narrow down our focus on how the way in which we communicate with others and respond to their needs and expectations of us.

This is a particularly delicate subject in intimate romantic relationships, as moods between both partners tend to be contagious.

In the introduction to this article, I mentioned that we may not always show as much enthusiasm as we feel when our partner shares something they are enthusiastic about.

It may be because our spirits are low, or simply, that we don’t have the patience nor empathy to come up with a more adequate response to the eagerness of our partner.

Or because it does not directly involve us, it simply does not move enough, and trying to respond in a way which would be proportionally positive, we feel, may come across as extravagant and inauthentic.

An example of this is set forth by the School of Life in an animated video called Why We Sometimes Try to Make Our Partner Sad.

The video sheds light on why, sometimes, for no seemingly explainable reason, one voluntarily decides to spoil the high spirits of their partners.

They may have come home with some fantastic news or simply, in a positive frame of mind, while we, on the other hand, have been feeling gloomy, preoccupied with something or even generally worn down.

The partner rushes in the front door grinning, all smiles, full of excitement, and -as it happens- some uncontrollable force takes control of our rational senses and brings us to shatter the mood with some morose, critical remark or with gaze soaked with indifference.

The partner’s elated feelings immediately come to a halt; they sense the negativity that is oozing from us and respond to it by means of conflict or, by simply shrinking away.

What’s going on?

The way we emotionally respond in these kinds of situations, that is, in which someone has something to share with us with great enthusiasm, but that we react with hostility speaks volumes about our attachment styles.

As the School of Life put it,

“On the surface, it looks like we are simply, monsters. But, if we look a little deeper, a more understandable though, no less regrettable picture, may emerge.

We are acting in this way because our partners’ buoyant and breezy mood can come as a forbidding barrier to communication.

We fear, that their current happiness could prevent them from knowing the shame or melancholy, the worry or loneliness that presently possesses us. We are trying to shatter their spirits, because we are afraid of being lonely”.

In this instance, the happiness of the other is experienced as a subtle form of betrayal, a renouncement to the empathy that they had once conceded to us, which transforms them into a type of human being, who we feel, may have never been acquainted with sadness at all.

This momentary distorted stance is of course, not true.

As the School of Life reminds us,

“every cheerful person has been sad, and that the buoyant among us, have by far the best chances of keeping afloat those who remain, emotionally at sea”.

If the happiness of the other makes us feel ill-at-ease, it is because it involves that we may have to positively acknowledge the fact that something external, which is not triggered by us, is eliciting a conspicuous exhilarated response.

The reason why toying with such a realization provokes such a hostility comes from the fear that we may no longer be at the center of their excitement, nor of their love.

Because we may be anxiously attached, the thought that they perhaps have discovered that we were not after all good enough for them, obsesses us.

And thus, at the height of their joy, we are stricken with horror: now may be the chosen moment for them to abandon us and leave us alone after having seen the most vulnerable parts of ourselves, which we may not have had the strength to disclose to anyone else.

In other words,

“The spoiling argument is a wholly paradoxical plea for love that leaves one party ever further from the tenderness and shared insight they crave […]. They are, childishly, but sincerely, worried that our happiness may come at their expense and are, through their remorseless negativity, in a garbled and maddening way, begging us for reassurance” (The School of Life, 2019).

This is not an apology for forms of communications and responding which seemingly defy logic.

Rather, it intends to be a conversation-opener about a recurring instance in social life which may appear insignificant and yet, as we will see plays a critical role in the sustainability of any relationship.

This is because different types of responses are directly linked with attachment styles.

Indeed, as a study has shown (Shallcross, Howland, Bemis, Simpson, & Frazier, 2011), adults with insecure attachments tend to ‘passively’ or ‘destructively’ respond to their partners when these share the details of a positive life event.

Such responses have the only effect of reinforcing insecure attachments as they fail to provide to the other partner a deep sense of emotional security that would be otherwise desirable.

Attachment Styles in Adult Relationships

The way in which we respond to the events that occur in the lives of our loved ones greatly depends on our attachment styles.

These are formed of the sum of relational expectations, needs, emotions, and behaviors that emerge from the internalization of a particular history of attachment experiences (Shaver et al., 2016).

While they are developed in childhood and are mediated by the relationship we have with our caregiver (the caregiver is a symbolic figure; in Western society children are usually raised in nuclear families, in other socio-cultural contexts, these are raised by the community at large), and they also span out throughout our adult lives.

Bowlby, who first developed a theory of attachment styles in relation to the nature of the infant-caregiver relationship, at a later stage of his life argued that these shaped human experience “from the cradle to the grave” (Doyle & Cicchetti, 2017).

Indeed, in the 1980s, Hazan and Shaver (1987) came to extend this relevance as demonstrated that the bonds that develop between adult romantic partners relate to the same motivational system that gives rise to the emotional bond between infants and their caregivers.

In other words, the behavior and degree of emotional availability of the care-giving adult will have inhibiting or disinhibiting effects on the child, who will develop a number of coping responses in order to navigate and make sense of the relationship with the caregiver.

As Debra Campbell writes (n.d.),

“how loved or unloved we feel as children deeply affects the formation of our self-esteem and self-acceptance. It shapes how we seek love and whether we feel part of life or more like an outsider”.

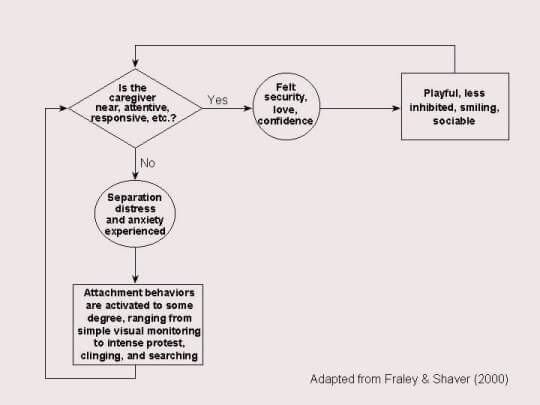

The graph below may clarify how attachment patterns are formed:

What happens is that as children become adults, they transpose the coping mechanisms they developed in childhood onto their romantic relationships.

Since the bond the child experiences towards the caregiver is so strong, and experienced as ‘love’, the tendency among adults -and also generally the cause of their misfortune- is that they seek partners who can provide them with the same treatment that was reserved for them by their caregivers when they were infants.

Most among us have strong views on what an ideal relationship would consist of; but very few understand that the reason why these never materialize is because instead of seeking more well-rounded, confident and independent partners, they pursue dysfunctional, insecure and anxiety-ridden characters instead, simply because, their version of love feels familiar.

This of course can lead a great deal of harm and exacerbate a person’s defenses, as while attachment styles are formed in childhood, they are either reinforced or altered in adult life.

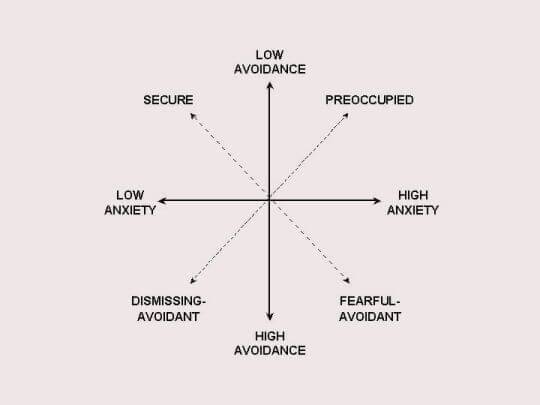

There are, in total, four attachment styles in romantic relationships.

- Secure

- Preoccupied-anxious

- Fearful-avoidant

- Dismissing-avoidant

A securely attached individual has the following characteristics:

- A positive view of him/herself and others.

- Low anxiety levels and active emotional involvement with others.

- Does not hesitate to turn others for support and advice.

- Does not take issue with being depended upon.

- Comfortable with spending time alone.

- Successful and fulfilling romantic relationships.

A preoccupied individual, on the other hand:

- A negative view of him/herself but a positive opinion of others.

- High anxiety levels while seeking out emotional intimacy.

- Fears that people they are attached to may not be available when needed or abandon them.

- Need others to feel complete or ‘rescued’.

- Generally clingy, jealous, demanding and possessive towards their partners.

A dismissive individual exhibits the opposite characteristics of the latter:

- A high opinion of him/herself but a general distrust of others.

- Perceive themselves as emotionally self-sufficient and independent.

- Prefers solitude over company.

- Avoid intimate relationships, either out of genuine disregard or because of a defensive mechanism against the possibility of rejection (Hepper & Carnelley, 2012).

- Has difficulties sustaining a long-lasting relationship, despite desiring a loving relationship.

- Unable to acknowledge their repressed needs and those of their partners.

A fearful individual, finally, exhibits the following characteristics:

- A blend of low self-esteem and a negative perception of others.

- High avoidance and anxiety patterns.

- Bottled up overwhelming emotions and defensive reaction to love, which result in an emotionally unpredictable behavior.

- A fear of getting hurt if they get too close to someone.

- A tendency to cling to their partner when rejected.

- A history of ‘rollercoaster relationships’ which are unstable and tumultuous (Firestone, n.d.).

A lucky majority proportion of the population are secure types: a study by Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van Ijzendoorn (2009) conducted among over 10,000 informants shows that 58% among them were securely attached. On the other hand, 23% were dismissing, 19% preoccupied and 18% fearful-avoidant.

Added up together, a big fraction of the population -42%- has to deal with rather dysfunctional forms of relatedness which, if unaddressed can have devastating effects on friendships, family and relationships.

Knowing where one stands can be a first step towards working towards a healthier form of thinking about oneself, or even, decoding better the cryptic communication styles of our loved ones.

If you are not sure what may be yours, you can take a quick test on this link to find out, and keep track of how your personality evolves over time.

Mindfulness and cognitive-behavioral therapy have been widely recommended by psychotherapists as particularly effective in addressing attachment issues, as research has shown that while attachment styles are usually profoundly internalized, these can be altered even in adulthood.

Campbell (n.d.) lists furthermore a number of steps that insecure types can individually take to work on their respective psychologies and how they navigate the sometimes-turbulent waters of their relationships:

- Seek flow in your life, by consistently working on the things you feel passionate about and are already good at. This can be a challenging one, involving quite a degree of soul-searching and patience, but effort and persistence always bears its fruits.

- Expand your horizons and leave your comfort zone. Building self-esteem, Campbell says, takes courage, discipline and resilience. The skills and strength developed in the process will serve you forever, and you will be amazed by what you can achieve just by yourself.

- Exercise. With physical strength, emotional strength usually comes along. This is because the nurturing process that takes place consciously during exercise, if consistent, will then also take place on a subconscious level. The hormones released during exercise also have a significant effect on wellbeing.

- Self-talk. A bit like meditation, this one involves becoming aware of your personal thoughts and the internalized negative beliefs you have about yourself (which usually are the internalized critical voices of others). It’s critical to understand that your thoughts are neither ‘true’ or ‘real’- that really, if you challenged them by repeatedly reminding yourself of your worth and achievements, while adopting a compassionate and caring mindset towards your shortcomings, you can really go a long way.

- Make the repressed conscious and reflect on the range of factors that may have shaped your psychology. Coupled with a compassionate attitude towards yourself, this approach will enable you to gain perspective on the deeply rooted “scars in your inner landscape” (ibid) and see how you may have fallen into certain dysfunctional patterns due to elements that ultimately, you cannot be held accountable for.

This leads us to consider the following questions:

- What are the long-term effects of negative responses on relationships?

- How can these be avoided?

- What are other responding styles?

- How are they interconnected with attachment styles?

A Look at Active Constructive Communication

Active-constructive communication refers to the way in which experiences, personal views or feelings are communicated in relationships.

As Ursula Le Guin writes (in Popova, 2015):

“Speech connects us so immediately and vitally because it is a physical, bodily process, to begin with. Not a mental or spiritual one, wherever it may end.

If you mount two clock pendulums side by side on the wall, they will gradually begin to swing together. They synchronize each other by picking up tiny vibrations they each transmit through the wall. […]”

Like the two pendulums, though through more complex processes, two people together can mutually phase-lock. Successful human relationships involve entrainment — getting in sync. If it doesn’t, the relationship is either uncomfortable or disastrous.

When you speak a word to a listener, the speaking is an act. And it is a mutual act: the listener’s listening enables the speaker’s speaking. It is a shared event, intersubjective: the listener and speaker entrain with each other. Both the amoebas are equally responsible, equally physically, immediately involved in sharing bits of themselves.”

In other words, the type of communication adopted in a relationship will determine the way in which the two clock pendulums swing, and whether this swinging will reveal itself to be either destructive or beneficial to the well-being of the clocks in the long-term.

The destructive ‘swinging’ will likely, for instance, fill the relationship with countless misunderstandings, anxieties, conflicts and negatively impact the mental health of the parties involved. It can also characterize itself by a complete absence of productive communication.

A constructive and active form of communication, on the other hand, consists of an approach in which in times of disagreement, the two parties involved can maintain a courteous, respectful and solution-oriented discussion, that strives to ensure that no one gets hurt.

Furthermore, it involves centering the relationship around positive experiences and affect, which results in a ‘win-win’ situation in which both parties involved feel like they are getting the best out of the relationship.

The long-term effects of such a centering are equivalent to those of active constructive responding in that it develops further the relationship by intensifying the bonds between both partners as well as the way in which both feel and think about the relationship.

What is Active Constructive Responding?

There is an assumption that one of the fundamental purposes of any relationship is to provide emotional and psychological support in times of hardship and responsive to each other’s needs (Collins & Ford, 2010).

This trope is culturally prevalent- as it appears for instance in Simon and Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled Water (2015):

“When you’re weary, feeling small/ When tears are in your eyes, I’ll dry them all / I’m on your side, when times get rough/And friends just can’t be found/Like a bridge over troubled water”

It also transpires the field of psychology as a wealth of studies investigate the way couples deal with distress, and how the coping methods enable the relationship to thrive in the long run (Logan & Cobb, 2016).

This emphasis on positive communication in negative contexts has, simultaneously led to the major omission of the impact of positive communication in positive settings.

This is surprising, according to Gable et al. (2004), given that positive events tend to happen at a higher frequency than negative events (Gable, Reis & Downey 2003).

Indeed, recent research has shown that responses to positive events have a higher impact on the well-being of a relationship than processes of relatedness in opposite scenarios (Gable, Gonzaga, & Strachman, 2006).

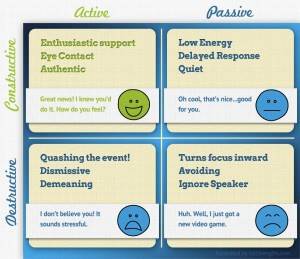

Psychologists have outlined four different types of responding:

- Active and constructive

- Passive and constructive

- Active and destructive

- Passive and destructive

Only one of them, however, actively plays a part in building a relationship.

So, what are they and what do they typically look like?

(If you would rather watch how these would look like in a performed actuation, have a look at this video put together by the University of Pennsylvania.)

Active Constructive Responding Episode 6

Consider the following scenario: Jane bursts into the living room and tells Mihail that she was just promoted at work. Her role involves new responsibilities as well as a higher pay. Jane has been waiting for this promotion for years; she could not be more head over heels and could not wait to share the news with Mihail, her husband.

In the living room, Mihail is fully absorbed by his novel. He is starting a new chapter in which the whole structure of narrative seems to finally be coming together. His communication style will determine the outcome of the scene.

Active constructive:

Mihail puts his book down and gets up from the sofa. He smiles, hugs Jane and tells her, “that’s wonderful! You are amazing. I always knew you would get it. All your hard work really paid off.” Jane’s smile only grows wider- she feels even more excited about the opportunity and feels very happy that the news is also making her partner feel so energized. She feels validated, understood and closer to Mihail.

Passive and constructive:

Mihail looks up at Jane, semi-interested, the book still in his hands, and says: “That’s good! We will now be able to go on holidays more often”. He smirks and goes back to his reading. Jane appreciates the acknowledgement but is disappointed that Mihail does not experience the same degree of excitement that she does.

Active and destructive:

Mihail throws his book on the sofa, gets up in an agitated fashion, looks at Jane straight in the eye while saying: “what? I thought you hated the company you are working for- and they are giving you a new role with a new contract? Unbelievable. Don’t accept it- I think you are not made for this kind of role, anyway.” On hearing this, Jane answers violently, which stirs up an argument.

Passive and destructive:

Mihail’s eyes do budge away from his book- he is captivated by the novel’s plot. Acting like nothing was ever said, he answers lazily: “Oh. When are we having dinner, by the way?”. Jane feels like her feelings are being completely dismissed; left speechless, she leaves the room and slams the door. Mihail recognizes that he could have put more effort into responding better but would not know how he would be able to do so anyway.

The reason why only the active constructive type of responding plays a part in building relationships is because, research has shown, that it is directly linked with commitment, satisfaction, intimacy, and trust (Gable et al., 2004).

By contrast, if a person cannot openly disclose positive or successful experiences with their partner because they have ‘learned’ that these will not be received with interest, enthusiasm or support, they will eventually feel insecure in pursuing or sharing with the other what genuinely makes them feel happy.

In the long-term, the bond of trust and intimacy will find itself eroded by the negativity oozed by the unresponsive partner, as the latter will degrade their sense of self-worth and confidence of the other.

What is Gaslighting?

Gaslighting is a practice located at the extreme end of the destructive-active responding spectrum: while it can take many expressions, it essentially involves the complete neglect and disregard of a person’s emotions and subjective understanding of reality, while simultaneously constantly either creating or highlighting their weaknesses.

It is a form of manipulation and control generally instrumentalized by narcissists and sociopaths (although it could be said lighter forms of gaslighting often surface in daily interactions or conflicts) for their own benefit.

The psychological and emotional toll on its victims are calamitous. If you would like to read more about what gaslighting practices may look like in a relationship, you may want to have a look at this article.

Positive-Active Responding

The positive-active type of responding has been defined as capitalization. We will be unpacking the concept at a later stage of this article. If you have realized that your responding style closely resembles to a passive or destructive type, then it may be a good idea for you to take up the challenge of changing what may be a deeply ingrained habit and see how it affects your relationship in the long term.

You may want to start setting yourself with a simple objective, for instance, to adopt an active constructive style for a whole day. While it may feel at first slightly unnatural, through repetition and practice, it will eventually come with more ease.

Don’t forget that active constructive communication is not only about the content of what you say but also the way in which you say it (which makes the difference between active and passive style). Also, pay attention to non-verbal cues, such as smiling, making eye contact, and that the body language you exhibit is positive.

How To Practice Selfless Listening

Erich Fromm’s six rules of listening (Popova, 2017) offers compelling and helpful insights regarding the mindset that ought to be adopted to excel at the art of selfless listening.

These are the following:

- Nothing of importance must be on his mind, he must be optimally free from anxiety as well as from greed.

- He must possess a freely-working imagination which is sufficiently concrete to be expressed in words.

- He must be endowed with a capacity for empathy with another person and strong enough to feel the experience of the other as if it were his own.

- The condition for such empathy is a crucial facet of the capacity for love. To understand another means to love him — not in the erotic sense but in the sense of reaching out to him and of overcoming the fear of losing oneself.

- Understanding and loving are inseparable. If they are separate, it is a cerebral process and the door to essential understanding remains closed.

Capitalization Psychology

Capitalization is term in psychology which describes the positive response which ensues from the sharing of one’s successes, which can also be defined as active constructive responding. The capitalization of positive emotions has also been described as a “process through which people derive associated benefits from sharing them” (Sas, Dix, Hart, & Su, 2009). It has proved itself to be pivotal in the quality and nature of any given relationship.

A study conducted by Shallcross et al. (2011) among 101 dating couples shows that informants who were:

- avoidantly attached, turned out to be less responsive if their ‘disclosing partner’ were anxiously attached. These also tended to downplay the responsiveness levels of their partners.

- anxiously attached underestimated their responsiveness when their disclosing partner were avoidantly attached. This data brought the researchers to the conclusion that insecurely attached individuals were less likely to be responsive to their partner’s disclosure of a positive event as well as more likely to downplay responsiveness in capitalization than more securely attached individuals.

In other words, the more insecurely attached a person is, the more likely they will negatively react to a success story, and if roles are switched, the more they will feel that the ways in which their partner responds to them is unsatisfying.

A secure person, on the other hand, will tend to respond in an active and constructive way, and perceive they’re partners attempts at capitalization as satisfying, which in turn will affect the durability and sustainably of the relationship. This shows us how important our attachment styles are in not only shaping the way we respond, but also the way in which we perceive the responses of our partners.

If capitalization primarily serves to nurture the relationship by means primarily focusing on the individual strengths of the parties involved, and this will lead to, as we have seen, greater commitment, intimacy and trust, it becomes clear how a more anxious or negative approach to the accomplishments of others would impact the relationship.

Why is Capitalization So Effective?

The science that underlies the reason why capitalization is so effective is because, according to Gable et al. (2004) sharing a positive event with others involves retelling the event, and this enables the sharing individual to relive and re-experience the positive emotions associated with the event.

Moreover, because the act of communication may involve rehearsal and elaboration, which in turn, prolong and enhance the experience itself by increasing its salience and accessibility in memory. What this means is that positive events, if communicated to others, will be better remembered than other positive events that were not communicated. But the benefits of capitalization do not limit themselves to relationships.

These may have independent and important associations with wellbeing and health (ibid), such as:

- a decrease in depression symptoms

- increase in daily self-esteem

- increase in perceived control over one’s life

- increased positive affect.

Martin Seligman on the Topic

Martin Seligman, the founding father of positive psychology, and the pioneer of the concept of the ‘politics of well-being’, has a strong stance on active constructive responding. In the following video, he argues that a mistake of couples’ therapy is that it excessively focuses on improving the way the negative elements of a relationship are managed, instead of learning from key behaviors and habits that enable great and successful relationships to thrive:

Active and Constructive Responding

“Marriage counselling consists of teaching partners to fight better. This may turn an intolerable relationship into a tolerable one. I, however, am interested in how to turn a good relationship into an excellent one” (Reflearn, 2008).

This critique is not any different from his own general view of psychology, which he says in his Tanner Lectures on Human Values at the University of Michigan, has been, historically “about what is wrong in life: suicide, depression, schizophrenia, and all the brick walls that can fall on you”.

In short, for far too long, he argues, psychology has dedicated itself solely to the study of misery, but not about what concretely makes life worth living (ibid).

According to Seligman, optimism can be learned; in a book with the same name (2006), he concludes that the epidemic of depression stems from the much-noted rise in individualism and the decline in the commitment to the common good.

This argument brings in a tremendous value to the way in which we behave in our relationships. What if instead of feeling down, unwanted and neglected simply because the fate of other’s seems more fortunate, we embraced the fact that the successes of others should not be interpreted as symptomatic of our failures?

Shifting away from individualism means to be able to nurture selfless responses to meet the needs of others and partake in habits that are pro-social rather than inhibited, bitter and destructive. A soothing concept to consider is that of the lottery of life – especially in the context of a media-driven society, which “constantly brings anomalies to our notice”.

Glossy, romantic ideals of life promoted by corporate culture distort our idea of the normal and cement in our minds the belief that it is not these constructions, but rather us, who are being unrealistic in our understanding of what life is and our expectations of it should be.

“If we could really see what love and work were like for most other people, we’d be so much less sad about our own situation and attainments”; and we would also feel more strongly about their achievements and good fortunes, ready to genuinely support them and cheer along.” (The School of Life, 2016)

This is a cry for a pessimistic type of optimism; which enables one to grasp the true miseries and sufferings of life, while acknowledging that what is in fact worthy of attention and celebration, are the instances which bring the best out of us and others.

Seligman advises:

“Take some time to reflect on your attitudes, check whether your responses are active and constructive and doing good rather than harm to your relationship” (Seligman as cited in Reflearn, 2008).

A Take-Home Message

In this article, we’ve looked at Active Constructive Responding and how it works in relationships. What is your take on this issue?

How do you think your attachment style is affecting your way of responding? What specific points do you think you can work on, to improve your relationship?

Let us know in the comments section below.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2009). The first 10,000 adult attachment interviews: Distributions of adult attachment representations in clinical and non-clinical groups. Attachment & Human Development, 11(3), 223-263.

- Boston, F. (2018). What is active and constructive responding? [Image]. Retrieved from https://gostrengths.com/what-is-active-and-constructive-responding/

- Campbell, D. (n.d.). Our attachment styles are blueprinted in childhood — here’s how to rewire yours. Retrieved from https://www.mindbodygreen.com/articles/how-to-develop-a-secure-attachment-style

- Collins, N. L., & Ford, M. B. (2010). Responding to the needs of others: The caregiving behavioral system in intimate relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 235-244.

- Doyle, C., & Cicchetti, D. (2017). From the cradle to the grave: The effect of adverse caregiving environments on attachment and relationships throughout the lifespan. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 24(2), 203-217.

- Firestone, T. (n.d.). Why do we keep ending up in the same kinds of relationships? The answer lies in our attachment styles. PsychAlive. Retrieved from https://www.psychalive.org/relationship-attachment-patterns/

- Gable, S. L., Gonzaga, G. C., & Strachman, A. (2006). Will you be there for me when things go right? Supportive responses to positive event disclosures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 904-917.

- Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., & Downey, G. (2003). He said, she said: A quasi-signal detection analysis of daily interactions between close relationship partners. Psychological Science, 14(2), 100-105.

- Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 228-245.

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(3), 511-524.

- Hepper, E. G., & Carnelley, K. B. (2012). The self‐esteem roller coaster: Adult attachment moderates the impact of daily feedback. Personal Relationships, 19(3), 504-520.

- Logan, J. M., & Cobb, R. J. (2016). Benefits of capitalization in newlyweds: Predicting marital satisfaction and depression Symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 35(2), 87-106.

- Popova, M. (2015). Telling is listening: Ursula K. Le Guin on the magic of real human conversation. Retrieved from https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/10/21/telling-is-listening-ursula-k-le-guin-communication/

- Popova, M. (2017). Erich Fromm’s 6 rules of listening: The great humanistic philosopher and psychologist on the art of unselfish understanding. Retrieved from https://www.brainpickings.org/2017/04/05/erich-fromm-the-art-of-listening/

- RefLearn. (2008). Active & constructive responding [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MU3y2ApnG7Y

- Sas, C., Dix, A., Hart, J., & Su, R. (2009, September). Dramaturgical capitalization of positive emotions: The answer for Facebook success? In Proceedings of the 23rd British HCI group annual conference on people and computers: Celebrating people and technology (pp. 120-129). British Computer Society.

- Seligman, M. E. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. Vintage.

- Shallcross, S. L., Howland, M., Bemis, J., Simpson, J. A., & Frazier, P. (2011). Not “capitalizing” on social capitalization interactions: The role of attachment insecurity. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 77-85.

- Shaver, P. R., Mikulincer, M., Gross, J. T., Stern, J. A., Cassidy, J. A., & Cassidy, J. (2016). A lifespan perspective on attachment and care for others: Empathy, altruism, and prosocial behavior. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed.), 878-916.

- Simon & Garfunkel. (2015). Bridge over troubled water (from the concert in Central Park) [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WrcwRt6J32o

- The School of Life. (2016). The lottery of life [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ds_hg40utKY

- The School of Life. (2019). Why we sometimes try to make our partner sad [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9f9fiNhXyuk

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (41)

- Coaching & Application (49)

- Compassion (27)

- Counseling (46)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (16)

- Grief & Bereavement (19)

- Happiness & SWB (35)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (21)

- Mindfulness (42)

- Motivation & Goals (42)

- Optimism & Mindset (33)

- Positive CBT (24)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (41)

- Positive Emotions (28)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (38)

- Relationships (31)

- Resilience & Coping (33)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Software & Apps (23)

- Strengths & Virtues (28)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (27)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (30)

- Types of Therapy (53)

What our readers think

Hi Nicole,

I understand active constructive responding has been proven to be the only positive way to respond to good news.

What are the best strategies to build relationships when someone delivers bad news?

Hi Hagit,

There’s an art to having difficult conversations with someone you care about. You can find some useful advice here, and there are also lots of books on the topic. Depending on the nature of the relationship, you can do a search for books about effective communication in marriages, friendships, employment settings, etc.

Hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager

Thank you! This is really helpful!

How can you practice positive active responding with a partner who getting excited about acquiring things and tends towards hoarding? When an excited response encourages the behavior?

Hi Erika,

Thanks for your question. There will sometimes be times when it is not appropriate to practice active positive responding. If you’re concerned about your partner’s acquiring/shopping habits, it’d be better to set aside a time to have an honest conversation about it. You can find some more information about how to do that here. My suggestion would be to pick a time for the conversation when you are both available to give your full attention. Avoid initiating the conversation when your partner has just come home with a new possession, but rather at a different time to make clear that this is an ongoing concern, not a concern you are raising on a whim. Avoid accusations and speak using language that emphasizes how the behavior is negatively affecting you emotionally/practically/financially, and that you’d like to discuss and arrive at a new normal around spending/acquiring things that you can both agree is fair.

I hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager