What Is Eustress? A Look at the Psychology and Benefits

In this article, we will explore the way in which eustress – what I call positive stress – may provide a long-lasting solution to the pervasive “distress” which may be creating harm in our lives.

“Imagine feeling capable of handling whatever life throws at you, without having to panic, overreact, or plan your exit strategy.”

Kelly McGonigal (2008) is a health nutritionist and professor at Stanford University and believes this is possible.

By delving into the inner-workings of stress, we can develop an understanding of how eustress may enable us to live more fulfilling, meaningful lives unconstrained by disproportionate neurological responses.

Before you start reading, we thought you might like to download our three Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises (PDF) for free. These science-based exercises will equip you and those you work with, with tools to manage stress better and find a healthier balance in your life.

This Article Contains:

What is the Meaning of Eustress?

Let’s start by looking at stress. Stress is a concept that is entrenched in our everyday lives and personal vocabularies.

Starting at a very early age, we are taught that adult life is ‘stressful.’ In this mindset, adulthood requires responsibility and achievement, which we accomplish by challenging ourselves and feeling stressed.

This traditional view of stress implies that if we are not stressed, we are not striving to become our best selves.

Until the ‘50s, stress was not an object of scientific attention. The golden age of the welfare state brought increased leisure time and growing criticism towards work. Thus, the Western world acknowledged stress only recently.

Because stress impacts our minds and bodies, it is crucial to study.

This article hopes that by understanding stress and how we perceive it, we can change the narrative of “all stress is bad for you.” As it turns out, associating stress with negativity can intensify our experience of stress itself.

Stress = Distress = Health Risk

Much of the world views all stress as bad, rather than viewing stress in its original meaning as “the non-specific responses of the body to any demand for change” (Selye, 1965).

The notion that stress is unhealthy and can lead to cardiovascular diseases, anxiety, and depression (Li, Cao & Li, 2016) has become part of the current global perception of stress.

With this prevailing belief, many humans have become stressed about stress. Definitely not the best stress management strategy.

This is because, as Le Fevre, Matheny & Kolt point out (2003), ”stress” has become a synonym for “distress,” a state of ill-being in which happiness and comfort have been surrendered.

Today, individuals often say that they are “stressed” when life feels chaotic, overwhelming, or tragic. An event like a heavy workload, a divorce, or an accident can feel too stressful to comprehend.

It is true: stress does push people into uneasy psychological states, but why? How do we live in the present and find inner peace when stress courses through our veins?

It is time for a deeper understanding of stress.

Stress is More than Distress

The idea that “stress is bad” is problematic, if not harmful, to our health. Belief plays a vital role in shaping physiological responses.

The widespread idea that “stress is bad” actually influences our physiological responses.

Stress may not be “good or bad,” but the perception of stress is. In a general sense, stress is just a conditioned response to a stressor, or a stressful event.

Stress helps us survive. It can heighten our senses and improve our performance with a given task or assignment.

But believing “stress is bad” can be detrimental in ways that stress itself, is not. Psychology, backed with empirical data, implores us to actualize our definition of stress by offering fresh insight.

If we change the negative perception of stress, we have the potential to transform our lives.

The Concept of Stress and Eustress

The notion of “stress” had been used for centuries in physics to explain the elasticity of a metallic object, and its capacity to endure “strain” (as for instance in Hooke’s Law of 1958). It had also been used by Hippocrates in Ancient Greece to denote a disease which combined elements of pathos (suffering) and ponos (incessant and relentless work).

By the turn of the 20th century, negative ideas of stress were widespread, largely due to the forces of industrialization and urbanization, since these forces shaped the collective psyche of Western society.

In 1956, the famous Hungarian endocrinologist Hans Selye published The Stress of Life. This instilled the concept of stress and stressor (to distinguish between the stimulus and the response) at the foreground of modern psychological research.

Introducing Eustress

Almost two decades later, in 1974, he redefines the terminology to establish a clarification between two different types of stress: eustress, and distress. Combining the Greek prefix eu-, (meaning good) with stress, eustress became the term used to define “good stress” in opposition with “bad stress.”

This was necessary for in non-roman languages, the translation of the term ‘’stress’’ was difficult.

In Chinese, for instance, the translation of the term consisted of the assemblage of two characters respectively representing ‘danger’ and ‘opportunity’, both combined meaning ‘’crisis.’’

By making the distinction between good stress (eustress) and bad stress (distress), Selye sought to show that stress, while being a reaction to a stressor, should not be always linked to negative scenarios.

Eustress = Good Stress = Health Benefits

According to Selye, eustress actually has emotional and physical health benefits.

It differs from distress with the following characteristics according to Mills, Reiss and Dombeck (2018):

- It only lasts in the short term

- It energizes and motivates

- It is perceived as something within our coping ability

- It feels exciting

- It increases focus and performance

On the other hand, distress, or negative stress, is characterised by:

- Lasting in the short as well as in the long term

- Triggering anxiety and concern

- Surpassing our coping abilities

- Generating unpleasant feelings

- Decreasing focus and performance

- Contributing to mental and physical problems

To embrace the idea of eustress, we have to understand our brain chemistry.

The Psychology of Eustress

Stress is essentially the outcome of the primal reaction known as fight-or-flight. Evolution has endowed humans with this reaction to fight against or flee from a potential danger (McGonigal, 2008).

The mechanisms of the fight-or-flight reaction are the following:

- A stressful event occurs, and an immediate response is triggered by the autonomic nervous system.

- The stress response activates the sympathetic nervous system, flooding the body with hormones such as cortisol and norepinephrine (McGonigal, 2008).

- These hormones heighten the senses, increase the heart rate, increase the blood pressure, and plunge the brain into a state of hyper-awareness.

- The part of the brain responsible for emotional calm and physical relaxation, the parasympathetic nervous system, is overwhelmed.

- A neurological cocktail of hormones and the overactivation of brain areas causes a burst of energy and focus, coupled with emotions such as anger, aggression, and anxiety.

In real danger, this reaction is very useful; it saved early humans from dying in the jaws of saber-toothed cats.

Unfortunately, our fight-or-flight brain chemistry has remained as a basic feature of human psychological processes, even when we do not need it.

If we perceive a stressful situation, no matter how serious the threat, this reaction ensues.

Whether the situation is actually life-threatening or not, the hormonal release is the same. This means it is possible to experience intense physical symptoms at the mere thought of something stressful.

Since the stressor is often only a perceived stressor, rather than a real one, changing the way the person relates to the stressor can influence the intensity of the experience.

If we do not want this fight-or-flight tendency to rule us, then it is crucial to recognize eustress.

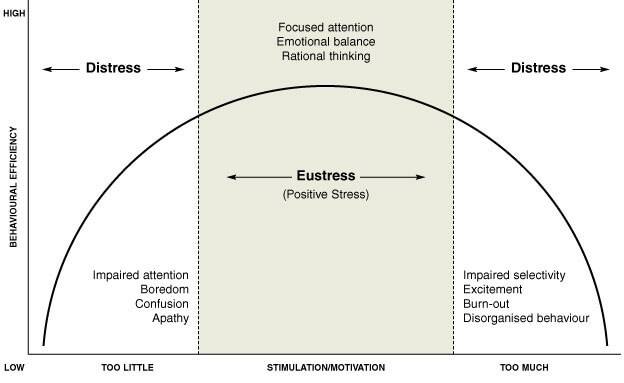

As the figure above indicates, eustress can lead to focused attention, emotional balance and rational thoughts. Distress, on the other hand, can cause impaired attention, boredom, confusion, apathy, excitement, burn-out and disorganized behavior.

So if a situation is not life-threatening, how do we can encourage our brains to perceive the situation as eustress, rather than distress?

Eustress, in its best form, can induce a state of flow. Like eustress, flow is a focused state often induced by a healthy dose of challenge.

So the question lingers – is it possible to transform distress into eustress? The short answer to this question is yes.

For a longer answer, we have to dive into what research and studies have to say about the topic (and for that, you’ll have to keep reading).

Examples of Eustress

It is difficult to have a universal list of situations for eustress, since each person perceives stressors uniquely. For example, many people might consider a divorce or break-up a source of distress, while others view it as a source of eustress and the possibility of a new beginning.

Lazarus argued that for a psychosocial situation to be stressful, it must be appraised as such (1993). In other words, if we view something as awfully stressful, it will flood our bodies with that rich cocktail of fight-or-flight chemistry.

Equally important, Suedfeld (1997) points out that some societally traumatic instances such as war, plagues or natural disasters, can cause stress and distress simultaneously.

On the one hand, distress could fuel anxiety, financial worries, and concern for other people’s well-being.

On the other, eustress could be triggered by positive forms of social engagement, resourcefulness, and communal support (Suedfeld, 1997). More so, the release of the oxytocin hormone during the eustress response could push people to seek or provide aid (McGonigal, 2014).

Although humans respond uniquely to stress, there are a range of stressors which tend to be experienced positively by most people, according to Mills, Reiss, and Dombeck (2018).

A few examples include:

- Starting a new romantic relationship

- Marrying

- Starting a new job

- Buying a home

- Traveling

- Going on a holiday

- Having a child

- Exercising

- Affording to buy something that is expensive

- Learning a new hobby

- Retiring

In addition to these bigger life moments, eustress also plays out in simple instances of daily life where a personal boundary is nudged:

- Cooking a complex meal

- Playing a challenging video game

- Going on a hike

- Riding a rollercoaster

All of these are sources of eustress.

As long as the pushing of this boundary feels pleasurable or enjoyable, it is eustress. If it doesn’t feel good – even in a remote sense – it’s distress.

Listen to your body – because what feels good often does good. Research in psychology shows that those who experience eustress on a regular basis reap a number of positive health benefits.

When subjective well-being increases each day, long-term positive changes also impact physical and mental health (Brule & Morgan 2018).

How does it work? Several theories try to answer this question.

One of them is control theory (Spector, 1998), which suggests that the experience of stress is conditioned by an individual’s perception of control to the stressor.

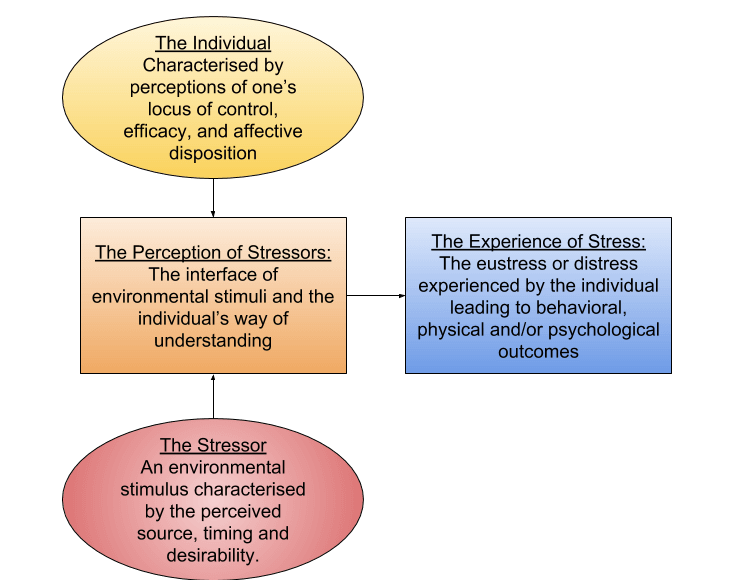

In this context, ‘control’ can be defined as a person’s agency and capacity to make choices (Ganster & Fusilier, 1989). The figure below helps to clarify this point:

Hence, the more control a person has over the environment with the stressor, the less likely their response to it will be negative and take the form of ‘distress.’

Many studies show, especially in work settings, that the more decision-making power an employee has, the greater their commitment to their role will be; this will translate into increased levels of performance and job satisfaction (Bond and Bunce, 2001; McFadden and Demetriou,1993; Wall et al., 1992).

To summarize, this theory argues that subjective perception plays a big role in determining the type of stress that will result from an environmental stressor, as well as a person’s emotional response to it.

Here, the more control a person has over the environment in which the stressor is located, the less likely that his response to it will be negative (and take the form of ‘distress’, along with the physical symptoms that characterize that type of stress response).

This point has been backed by a number of studies that show, notably in the work settings, that the greater decision-making power of an employee is, the greater his commitment to his role will be.

This will translate into increased levels of performance and job satisfaction (Bond and Bunce, 2001; McFadden and Demetriou,1993; Wall et al., 1992).

Research and Studies

Eustress might be the key for us to transform negative stress into healthy stress.

Benefits and Positive Effects of Eustress

Ted talk: How to make stress your friend | Kelly McGonigal

A useful introductory video on the subject is a Ted Talk by Kelly McGonigal (2013), who explains how in her career as a health psychologist, her biggest mistake was to tell people that stress was awful, and “something that makes you sick.”

While this came from a personal goal to make people happier and healthier, she realized that she was instead doing “more harm than good.”

This realization also coincided with the publication of a study for which 30,000 interviews were conducted in the United States, over five years, asking informants the following question: do you believe that stress is harmful to your health?

The results were astounding.

Those who had replied “yes” (nearly 186 million U.S adults), exhibited worse health and mental health outcomes than those who had answered “no” (Keller et al., 2012).

This relates to earlier points around the perception of stress: believing that stress is harmful can impair people’s overall mental and physical well-being. For McGonigal, this study was a revelation: it highlighted how belief influences health outcomes, and in this context, the ways people experience stress.

McGonigal became an unconditional advocate of eustress, advising people to accept a given stress response, and rethink it as helpful, as opposed to detrimental.

This approach, she argues, works best. Over time, they can develop a mindset equipped to deal with challenges rather than fear them. This acceptance builds resilience.

Resilience benefits people and empowers them to feel that they can pursue what creates meaning in their lives, while trusting their strength to handle potential stressors.

This is a tremendously empowering asset.

In McGonigal’s words, “you create the biology of courage” when you interpret the physical symptoms of stress – such as a pounding heart – as a “call for action,” as opposed to a call for dread.

A Look at Eustress and Flow

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). Flow, the secret to happiness

Described as “the ultimate eustress experience” (Dubbels, 2017), flow is on the upper end of the stress spectrum, far from distress with all its negative components. Positive psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi describes flow as the secret to happiness (2004), often experienced as a state of intense clarity and focus.

This peculiar state makes you “know exactly what you want to do from one moment to the other. You know that what you need to do is possible to do, even though difficult; a sense of time disappears, you forget yourself, you feel part of something larger.”

This somewhat surreal state can be achieved by composing music, writing, having a passionate conversation, developing an engineering project, and many other ways.

How does this connect to eustress?

As we have mentioned, the brain responds to stressors differently depending on the source, timing, control of the person, and their disposition – but if the stressor is perceived as manageable, meaningful and desirable, then a person will likely develop a predisposition to enter a state of flow.

In flow, all of our energy filters into the resolution of a given problem, and the mastering of a skillset.

Many workplaces and sports arenas offer concrete cases of flow. Both environments can generate stress in the body, and if a delicate balance is achieved, it can arouse eustress.

As this article conveys, eustress in either of these settings can optimize performance.

The Eustress Scale: Applications in Business and the Workplace

The business sector quickly understood the utility of eustress, and the potential to maximize the performance of employees while ensuring that they are not being overwhelmed by their given tasks.

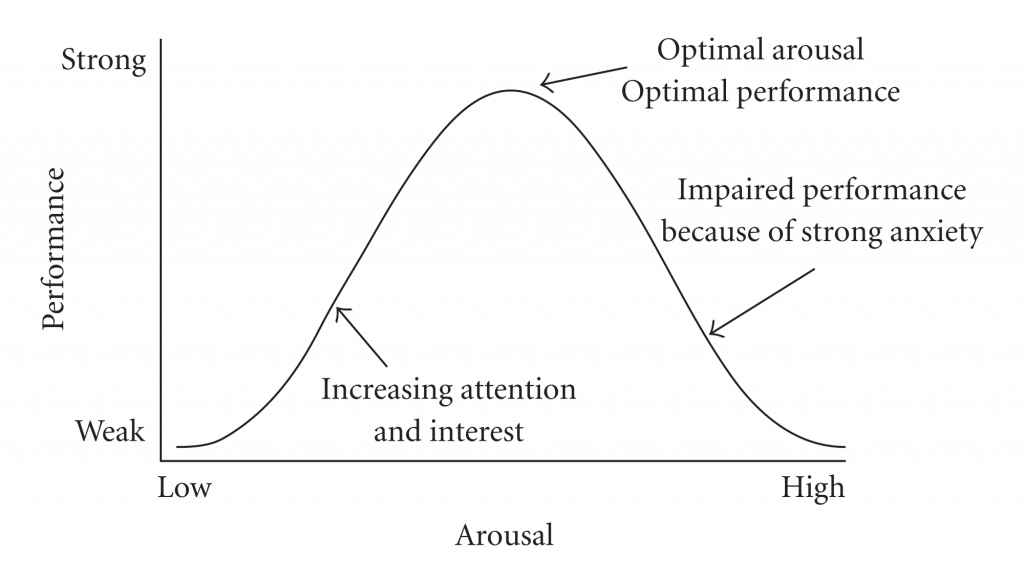

The balance between optimal arousal and performance was sketched out in the Yerkes Dodson law dating from 1908 (see the figure below) and shows that beyond a certain threshold, performance can become impaired due to excessive anxiety.

The Yerkes Dodson Law, which frequently appears in basic management texts (e.g. Certo, 2003; Gardner & Schermerhorn, 2004), affirms that individuals can only really thrive under certain conditions. This balance often needs people to feel that their responsibilities are accessible yet stimulating, as opposed to overbearing hindrances.

At its worst, according to Gavin & Mason (2004), job stress is felt when the demands of the work exceed the workers’ belief in their capacity to cope.

As such, research has shown (Brule & Morgan 2018) the benefits of workplaces supporting the environment of eustress. Well-managed eustress can allow corporate interests to arise through the optimal performance of their employees.

One of the main problems with eustress in the business context, is that it has been misused and lacked crucial monitoring of the workers’ adjustment to their tasks and stressors.

As Melody (2018) points out, “the idea of using anxiety to enhance performance gained traction in the face of the economic deregulation of the 1990s and the resulting competitive pressure.”

While anxiety is a key element necessary to any productivity, too much of it causes distress.

It is likely that Melody was referring to distress rather than eustress, since zero stress (if taken as a physiological response) in a workplace may also be detrimental.

If employees don’t feel challenged by the assigned tasks, boredom often arises (Brule & Morgan 2018). This can start a vicious cycle of dissatisfaction in which employees feel frustrated with their performance, with the work itself, and with themselves. This can lower self-esteem, and trouble the workplace.

The lack of stimulation or ‘stress’ can cause boredom and depression in other areas of life too.

For example, as McGonigal (2008) illustrates, people who try to avoid all stress often feel a lack of life’s essential components. She goes on to explain that “while excess stress can take a toll on you, the very things that cause it are often the same things that make life rewarding and full.”

McGonigal encourages people to reflect on “the pressures in your life: family, work, having too much to do. Now imagine a life without those things. Sounds ideal? Most people don’t want an empty life. They want to possess the skills to handle a busy and, yes, even complicated life” (2008).

Some degree of arousal is needed for individuals to perceive their work to be worthy of esteem and stimulating. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi explains that (2004), “arousal is the area where most people learn from because that’s where they’re pushed beyond their comfort zone.”

In sum, a compromise is mandatory. Human resource managers need to establish reasonable boundaries and schedules, cultivate a positive mindset at the heart of the workplace, and support a healthy working space.

Eustress in Sport Psychology

Similar to business managerial models, the world of sports has applied the benefits of eustress to optimize individual and team performance.

Competitive sports tend to be demanding, not only physically, but also mentally. The pressures of winning, managing public image, and maintaining a positive social presence can be challenging.

For many athletes, the pace of life is intense. So what does this have to with eustress?

If an athlete experiences this intensity as suffering (distress) or enjoyment (eustress), the entire physiological experience changes.

It is a fragile balance, between optimal performance, and optimal emotional and physical health.

To manage this, players often enter a state of flow at the peak intensity of competition and also maintain a belief that by doing this activity, they are ‘part of something bigger.’

In some ways, when athletes master a stressor with their physical and mental strength, they capture what it feels and means to be alive and overcome challenges. It is no wonder that many cultures worship their sports teams and athletes.

The warrior-like values that lie at the heart of sports can be a source of inspiration for the rest of society.

We seem drawn, as humans, to examples of control over perceived threats. Perhaps this is why people internalize the victories of teams they cheer, and after a winning game, feel influenced and changed by them.

“Check your thoughts, challenge them and change them”

Dr. Hopley

The Neuropsychology of Performance Under Pressure | Dr. Philip Hopley

Eustress vs Distress Worksheet

Can you differentiate between the different types of stress you experience on a daily basis? If you feel like distress frequents your life more than eustress, then you’re at the right place.

Here is a worksheet we put together to help you identify positive and negative forms of stress that your body generates when exposed to certain situations and emotions.

Sometimes the best way to make sense of stressors is by writing about them and exploring the ways they affect our lives.

To understand your balance of distress and eustress, a first step is to keep a ‘stress diary.’ This is a diary solely dedicated to writing about your experiences of stress. It can be a place for you to vent and process intense life experiences.

If you don’t know where to start, try to remember moments in which you felt panicked, overwhelmed, or let down. Recall a demanding situation or a nightmarish scenario, and how it felt to experience. Or, reflect on a time when all odds seemed stacked against you—and yet you succeeded.

Write about how those moments felt psychologically and physically. If you can remember them, make a list of the different thoughts that were going through your mind at that time.

When you are done, review your diary, and identify examples of eustress and distress, based on the following definitions:

- Eustress: a situation which feels stressful but you feel like you can handle it, despite feeling challenged; it makes you have positive thoughts about life and yourself.

- Distress: a situation that feels overwhelming and unlikely to result in satisfactory outcomes; you feel like your health is deteriorating and have negative thoughts about life and yourself.

| EUSTRESS | DISTRESS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

| _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

| _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

| _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

Create a table with four columns, using ‘Eustress’ and ‘Distress’ as headers, and leave two blank columns after each.

Can you fit an instance you wrote about in the diary in the columns?

Great. Now try to enter as many as you can until you have your list of experiences.

Now, next to both ‘Eustress’ and ‘Distress’ respectively, put the headers ‘physical and mental symptoms,’ and ‘stressors.’

Can you remember what symptoms you experienced in both moments of eustress and distress? What do you think the stressors were? Fill in as much as you can in the corresponding columns.

| EUSTRESS | Physical and mental symptoms | Stressors | DISTRESS | Physical and mental symptoms | Stressors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I can only thrive in high-pressure environments | This type of stress makes my heart pound, my thoughts race and I feel energized | The heavy workload uncertainty and constant feedback | Giving presentations makes me feel ill | I start sweating, feeling nausea and anxious | Public speaking, a fear of making a mistake or embarrassing myself |

| Taking the airplane is a difficult thing to do | I get stomach ache, I feel nervous, irritable | Losing control, feeling powerless, fear of heights | |||

| _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

| _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ | _______ |

You have your table – now, look at the ‘distress’ column and highlight the areas of distress that trouble you the most.

Do you notice a pattern that repeats itself regarding the distressed situations? For example, do you experience distress when you feel like things are going out of control, or when you have to carry out a presentation in front of an audience?

The goal now is to find ways to convert distress into eustress.

How you physically and mentally respond to a stressor depends on a range of factors, but mostly your mindset and the kind of lifestyle you live. A lifestyle adjustment may include:

- Adopting a better diet

- Exercising more

- Sleeping better

- Meditating regularly

These can change, minimize and even eliminate a stressor.

A good support system and a healthy sense of self-esteem also are essential elements that keep stress levels low.

But even if such changes are made, the stressor and distress can persist—what matters is what you believe about the stressor and how it affects you.

This shift in examining our beliefs around stress can change whether your mind interprets the stressor as an ‘emergency threat’ or not.

Other coping strategies can be adopted ‘in the moment’ too. For example, breathing techniques release oxygen in the brain; this relaxes the muscles, slows the heart and breathing rate, and changes the body’s physiological response.

In this way, distress can be tackled and unlearned through a process in which you learn to react to the same stressors with positive emotions like gratitude, hope, and goodwill (Selye, 1987).

A Take-Home Message

Is it easy to change our reactions to stressors? No.

Is changing our reactions possible and vital for our health? Yes.

Positive self-talk and reaffirming statements to yourself can be extremely powerful and can disintegrate negative beliefs of certain stress responses.

Try different methods and see what works and what doesn’t for you – but next time you talk about your stress, let’s hope that you will not be referring to the ‘distress’ kind of stress, but your abounding eustress, instead.

For your own health, and well-being, as well as in many social and workplace settings, eustress has a lifetime of benefits waiting for you to explore.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Stress & Burnout Prevention Exercises (PDF) for free.

- Brulé, G., & Morgan, R. (2018). Working with stress: can we turn distress into eustress? Journal of Neuropsychology & Stress Management, 3, 1-3.

- Dubbels, B. R. (2017). Gamification Transformed: Gamification Should Deliver the Best Parts of Game Experiences, Not Just Experiences of Game Parts. In Transforming Gaming and Computer Simulation Technologies across Industries (pp. 17-47). IGI Global.

- Certo, S.C. (2003). Supervision: Concepts and skill-building. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Ganster, D. C. & Fusilier, M. R. (1989). Control in the workplace. International review of industrial and organizational psychology, 4, pp.235-280.

- Gardner, W. L., & Schermerhorn, J. R. (2004). Unleashing individual potential. Organizational Dynamics, 3(33), 270-281.

- Gavin, J. H., & Mason, R. O. (2004). The Virtuous Organization:: The Value of Happiness in the Workplace. Organizational Dynamics, 33(4), 379-392.

- Jones, J. G., & Hardy, L. (1990). Wiley series in human performance and cognition. Stress and performance in sport.

- Keller, A., Litzelman, K., Wisk, L. E., Maddox, T., Cheng, E. R., Creswell, P. D., & Witt, W. P. (2012). Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. Health Psychology, 31(5), 677.

- Lazarus, R.S. (1993). From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual review of psychology, 44(1), pp.1-22.

- Le Fevre, M., Matheny, J., & Kolt, G. S. (2003). Eustress, distress, and interpretation in occupational stress. Journal of managerial psychology, 18(7), 726-744.

- Li, C. T., Cao, J., & Li, T. M. (2016, September). Eustress or distress: An empirical study of perceived stress in everyday college life. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing: Adjunct (pp. 1209-1217). ACM.

- McGonigal, K. (2008). Tame your stress. Yoga Journal, 275, 82.

- McGonigal, K. (2013). How to make stress your friend. Ted Global, Edinburgh, Scotland, 6, 13.

- Mills, H., Reiss, N., & Dombeck, M. (2018). Types of Stressors (Eustress vs. Distress). Retrieved from https://www.mentalhelp.net/articles/types-of-stressors-eustress-vs-distress/

- Rosch, P. (2018). Hans Selye: Birth of Stress. Retrieved from https://www.stress.org/about/hans-selye-birth-of-stress/

- Selye, H. (1956). The stress of life.

- Selye, H. (1965). The stress syndrome. The American Journal of Nursing, 97-99.

- Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1998). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. Journal of occupational health psychology, 3(4), 356.

- Suedfeld, P. (1997). Reactions to societal trauma: Distress and/or eustress. Political Psychology, 18(4), 849-861.

- World Health Organization, & Commission of the European Communities. (1986). Environmental health criteria (No. 53). World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2018). WHO | Stress at the workplace. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/

- Wilding, M. (2018). Please Stop Telling Me to Leave My Comfort Zone. Retrieved from https://anxymag.com/blogs/home/comfort-zones-melody-wilding

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (41)

- Coaching & Application (49)

- Compassion (27)

- Counseling (46)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (16)

- Grief & Bereavement (19)

- Happiness & SWB (35)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (21)

- Mindfulness (42)

- Motivation & Goals (42)

- Optimism & Mindset (33)

- Positive CBT (24)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (41)

- Positive Emotions (28)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (38)

- Relationships (31)

- Resilience & Coping (33)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Software & Apps (23)

- Strengths & Virtues (28)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (27)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (30)

- Types of Therapy (53)

What our readers think

Hi,

I’m currently working on a writing sample for my master in Psychology and I’m talking about stress, stressor’s and I would like to cite some of this article about Eustress.

May I have the references of this article or perhaps the PDF version?

Thank you.

Hi Danayth,

Yes! Although we don’t provide PDF downloads of our articles, you’re more than welcome to cite it. Here’s how you’d do that in APA 7th:

Tocino-Smith, J. (2021, December 10). What is eustress and how is it different than stress? PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/what-is-eustress/.

If you scroll to the end of the article, you’ll also find a button you can click to expand the reference list.

Hope that helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager

Hi , Juliette !

Thanks for a very absorbing useful article.

I took time out from my schedule to return back to it. Great write up!

I would love to share the links on my site with all citations and references in my write ups if it’s ok with you.

Dr S A Siddiqui

India

Hi Dr. Siddiqui,

So glad you enjoyed the article! 🙂 Yes, feel free to refer to and cite this post in your work.

Good luck with it!

– Nicole | Community Manager