What Is Peak-End Rule? Theory & 14 Real-Life Examples

Update March 2019: This is article on peak-end theory has been updated and extended.

Update March 2019: This is article on peak-end theory has been updated and extended.

We’ll walk you through the psychology behind the peak-end theory, relevant research supporting it, and how it relates to pain and pleasure. As you will see, implications for understanding the peak-end theory can be game-changing, as it impacts many areas of life.

It may surprise you to hear how biased we are in how we form memories from our experiences. Even when we think we are recalling facts about an experience, our recollection of events is typically incomplete and heavily dependent upon the feelings we were having during the experience.

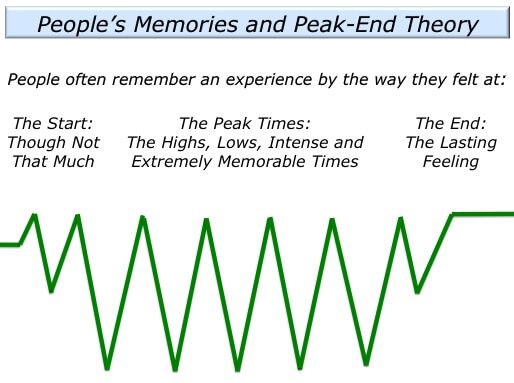

It seems that our memories of positive and negative experiences are dependent upon two things: what we were feeling at the most extreme (peak) point and how the experience ended. Our memories are typically not an average of the experience or the amount of time we were engaged in the situation.

This psychological heuristic explains why we can actually be irrational in our recollection and memory of events. It also suggests that our memories consist of a series of highlights rather than a thorough record of facts and events.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is Peak-End Theory?

The peak-end theory is a psychological rule in which an experience is evaluated and remembered based on the peak (most intense) point of the experience and/or the ending of the experience. It seems our recollection of events is impacted greatly by this interpretation of events experienced rather than the experience as a whole.

Peak-end theory was created by the Nobel Prize-winning Israeli psychologist Daniel Kahneman. His definition is as follows:

“The peak-end rule is a psychological heuristic in which people judge an experience largely based on how they felt at its peak (i.e. its most intense point) and at its end, rather than based on the total sum or average of every moment of the experience.”

Chip and Dan Heath also explore this concept in their book ‘The Power of Moments: Why Certain Experiences Have Extraordinary Impact.‘

According to the Heaths:

“When people assess an experience, they tend to forget or ignore its length. Instead, they seem to rate the experience based on two key moments: (1) the best or worst moment, known as the peak and (2) the ending [..] What’s indisputable is that when we assess our experiences, we don’t average our minute-by-minute sensations.”

They suggest that a peak moment requires at least one of the four elements below, with the best having all four:

- Elevation: these are moments of happiness that transcend the normal course of events through sensory pleasures and surprise

- Pride: these are moments that capture us at our best; whether it be moments of achievement or moments of courage

- Insight: these are our eureka moments; they change our understanding of ourselves of the world and give us a moment of sobering clarity

- Connection: these are moments which are social in nature; think weddings.

As it turns out, even how long an experience lasts has little impact on the memory that is formed. Kahneman and Fredrickson named this discovery duration neglect.

Duration neglect is the psychological recognition that people’s judgments of the unpleasantness experiences depend very little on the duration of those experiences (Kahneman & Fredrickson 1993).

A Look at Daniel Kahneman’s Work

The peak-end rule was studied by Kahneman & Tversky in 1999, as they concluded that people remember experiences essentially based on how they feel at its peak and its end, rather than their experience overall. Multiple studies support this cognitive bias for human errors in memory (Kahneman & Tversky 1999)

Kahneman attributes this cognitive tendency to evolutionary purposes. He states, “Memory was not designed to measure ongoing happiness, or total suffering. For survival, you really don’t need to put a lot of weight on duration of experiences. It is how bad they are and whether they end well, that is really the information you need as an organism.”

Kahneman describes two types of “selves,” the experiencing self and the narrating self. The experiencing self is our moment to moment awareness and being present. This mode of thinking is intuitive, quick, and unconscious. The experiencing self does not remember events, and each moment of the experiencing self lasts 3 seconds.

The narrating self is what collects and integrates our experiences into a story. It reviews our experiences and creates narratives that we experience as our memory. Our narrating self does a lot of editing and interpretation. During this process, changes in our stories occur.

As mentioned, the duration neglect is a critical component of peak-end theory. According to Kahneman, what gets remembered are significant, intense moments of the experience, regardless of the length of time.

The length of time of an experience does not get interpreted to our narrating self. It seems we do not make rational calculations of our experiences of pain or pleasure. Our memories are defined by the intense moments or peaks as well as the ending rather than how we felt most of the time of the experience.

Kahneman identifies the difference in the perspective of these two “selves” is how time is interpreted. Research indicates that the length of time of an experience has little effect on the real memory. Kahneman describes how the length of a vacation has little impact on how it is recalled.

In other words, a two-week vacation has little benefit over a one week vacation because new memories are not interpreted and added to the narrative or recollection of the experience.

The Psychology Behind Peak-End Theory

Cognitive biases change the way we remember circumstances. Our brains cannot remember the details of every experience we face. Our brains have ways of finding more efficient ways to process the many data points encountered at any given time. As a way to prioritize our memories, we tend to create highlights.

The peak-end effect is a cognitive shortcut our brains use by focusing our memories on the most intense aspects of an experience and what the ending is like.

The Psychology of peak-end theory is based on cognition. Our brains do not act as computer operating systems, as we have limits to how much we can process and remember. Our cognitive processing system creates methods to be more efficient in sorting through incoming information, integrating, processing, and making decisions.

The peak-end rule suggests that our memories are not comprehensive pictures of experiences. We are limited in the amount of detail our memories will hold. To compensate, our tendency is to recall the peak experiences or highlights, as well as the endings.

From an evolutionary standpoint, it makes sense that we would remember extreme experiences, positively or negatively. Establishing memories of negative experiences help us avoid similar situations in the future. Being able to recall positive experiences can help guide us to seek these situations out again.

It is a paradigm for making decisions based on the most intense aspect of the situation or how it ended. We tend to form judgments about an experience based on how we are feeling at these key points in time. This theory was developed in part to explain the irrationality involved in some forms of human behavior and memory recall.

Studies support the duration neglect theory, as it has been shown that the average amount of pleasure or discomfort experienced does not predict someone’s judgment of that experience.

The peak-end rule allows us to maximize our brainpower and conserve cognitive energy. It helps us avoid spending brain capacity to memories that are irrelevant and not needed. Findings supporting peak-end theory suggest that a small improvement near the end of an experience can radically shift one’s perception of the event.

What Does the Research Say?

The psychological rule that determines evaluation and memory of experiences has been studied in a diverse set of circumstances. Many studies have proven to support the peak-end theory. Individuals often will select exposing themselves to more pain or discomfort if the situation ends on them experiencing slightly lesser pain or discomfort. The length of time of the discomfort does not appear to be a factor in these choices.

The peak-end rule was initially explored in a study that involved exposing participants to short, plotless film clips (Fredrickson & Kahneman, 1993). The clips ranged in duration and affective impact (amputation, coral reef views, etc). Two versions of each film were viewed, one being roughly three times longer in duration.

Participants viewed the long version of the eight clips and the short version of eight other clips, then ranked the films from memory. Participants’ evaluations post-viewing was determined by a weighted average of “snapshots” of the actual effective experience, despite the duration.

According to a study done by Miron et al (2009), memory-experience gaps exist for both pleasant as well as unpleasant emotions. It was noted that the gaps were more significant for unpleasant emotions. People recalled being more angry and sad than they reported through measures of the actual experience.

Chajut and associates (2014) explored the relationship between the experience of labor pain and its recollection 2 days and 2 months post-delivery. Despite the extreme discomfort related to childbirth, the memory of the labor pains was biased toward the average of the peak pain and the ending pain.

Duration of the labor and delivery were not relevant factors on the recollection of the pain experienced. Researchers compared the experience of mothers whose labor ended with or without epidural analgesia. Results support the findings that the level of pain toward the end of an experience strongly impacts the way the whole event is remembered.

Hoogerheide et al (2017) explored the peak-end effect with children and how they experience and remember peer assessments. In their study, the peer assessments, particularly the negative evaluations represented an intense emotional experience. Research indicated that similar to adults, children are sensitive to the ending of emotionally intense experiences.

It has also been explored how applying this paradigm impacts contexts for learning. Recent studies support the peak-end effects for the case of students studying foreign vocabulary for a test (Finn 2010) as well as taking difficult math tests (Finn & Miele 2016).

Egan et. al (2016) even explored the origins of the peak-end theory, developmentally and evolutionarily. They assessed three populations – human adults, human children, and capuchin monkeys. They structured events in order to maximize their experience by picking the sequences with the best endpoint. Researchers discovered that capuchins preferred a food reward with the most delicious part distributed at the end rather than the beginning.

They showed a marginal preference for a reward with a short but high peak to a reward with a longer, yet less intense peak experience. The 3 populations were evaluated for how they structured their sequences using high peaks and ends to maximize their pleasure.

Results indicated that all 3 of the populations did not construct their experiences in ways that maximized their pleasurable gains. They did not make adjustments in order to enhance hedonic experiences.

Peterson & Kozhokar (2017) explored the perceptions of workload ratings. Results confirmed that subjective workload ratings are also impacted by the peak-end effects. Participants were asked to complete the same three tasks presented in a different order. Then they were asked to rate the workload of the whole session.

One of the tasks was created to be more challenging than the other two requests. When the most challenging task was requested last in the session, there were higher ratings on the subjective workload scales. However, researchers noted that while the scores were higher, the increase did not reach statistical significance.

Studies conducted by Hoogerheide and Paas (2012) provided support for the peak-end rule for subjective ratings when configuring learning tasks, as more difficult tasks are placed at the end of a learning experience.

Adding discomfort to an experience will not improve the episode. However, adding a segment of decreased discomfort to an unpleasant or painful experience improves its overall evaluation. Varey and Kahneman (1992) explored how.

14 Examples of the Peak-End Rule

We can consider many daily or common experiences, both painful and pleasurable demonstrating the peak-end rule. Here are some quick examples highlighting the peak-end effect.

Positive endings can detract from an overall negative experience.

- A classic example is childbirth. Memories of childbirth are strongly influenced by the peak and the ending rather than the duration of the labor. The positive memory of a baby being born can outweigh the impact of the length of the pain endured during the process.

- For example, if you attend a concert with poor sound quality or performance, yet the concert ends with your favorite song, your memory of the experience overall will be more positive.

- If you have a terrible meal at a restaurant, yet end with a delicious dessert, your memory of the meal is apt to be more favorable.

- A sports season that was challenging or stressful ends in a championship win. Chances are, the team will have more positive memories based on this single, emotionally intense experience of winning a big game.

- Funerals have been described as a manifestation of the peak-end rule. Even with a lifetime of experiences about someone, we end with hearing positive things about their lives, likely affecting our overall memories of them.

- Duration neglect can be demonstrated in how we form memories of vacations. Extending vacations appears to not have a positive impact on the memories formed from the experience. A 2-week vacation will produce similar positive memories as a 1-week vacation since there are not diverse memories being formed. So, longer vacations are not necessarily remembered more fondly than shorter trips.

Negative endings can also detract from the overall impression of an experience, even if it was essentially positive or pleasurable.

- A bad flight experience on the way home from a vacation can take away from the overall trip, even if the vacation was essentially positive.

- You may play a great round of golf, yet things fall apart on the 18th hole. You are likely to be left with a negative feeling of the round, even though the first 17 holes went well.

- If you experience a positive date night with your spouse, yet end with a two-minute disagreement, the argument will taint your memory of the whole evening.

- A breakup of a relationship is also a common example, as we may vividly recall a heartbreaking or painful breakup.

- Ending a class that you mostly enjoyed, yet ended up with a failing grade will tarnish your overall experience of the class.

Peak experiences that are not endings also influence our recollection of events.

- For example, close games with intense moments such as scoring a big goal or making a mistake during the game will impact the memory formed.

- Peak experiences involve emotional intensity. An example could be someone who essentially is happy in their job yet has a very negative experience with their boss. If they have experienced fear or anxiety due to a boss ridiculing, yelling, or humiliating, chances are it will impact their recollection of the job overall.

- Situations, when we are faced with extreme fear, will color our memories significantly as well. If we have a close call or get in a car accident, it will impact how we remember a road trip regardless of what else occurred.

Pain and Peak-End Theory

Our memories of painful experiences are likely to be inaccurate. It is also understood in the world of psychology that negative experiences are recalled more vividly than positive events.

Kahneman, Fredrickson, Schreiber & Redelmeier’s (1993) impactful research study also provided key evidence for the peak-end rule, especially as it relates to our memory recall of painful experiences. Participants in the study were subjected to two different versions of an unpleasant experience.

- The first trial had subjects submerge a hand in 14°C water for 60 seconds.

- The second trial had participants submerge the other hand in 14°C water for 60 seconds yet they then kept their hand underwater for an additional 30 seconds, during which time the temperature raised to 15°C.

Participants were asked to select which trial they would like to repeat. Interestingly, participants were more willing to re-do the second trial, even though they were exposed to uncomfortably cold temperatures for longer. Researchers concluded that participants chose the second, longer trial because they preferred the memory of it or disliked it less. In this study, it was supported that people judge experience how the event ends.

Much of the research on peak-end theory involves studying medical procedures. Kahneman, Katz & Redelmeier (2003) evaluated how patients responded to colonoscopy procedures.

In their study, two groups experienced colonoscopies. One group had a standard procedure and in the second group, after the procedure was completed, the scope was left inside, unmoving, for 20 additional seconds. Probes are not as unpleasant unmoving as they are when moving. The second group rated their experience with the colonoscopy slightly better than the first group. Researchers attribute to the difference to the second group experiencing a milder ending, therefore recalled it as a less unpleasant experience.

Schreiber and Kahneman (2000) showed that ratings of unpleasantly loud sounds showed clear peak-end effects.

Results from the cold water submersion study were also confirmed in an experiment using unpleasant noises (Schreiber and Kahneman, 2000). Participants were exposed to a series of irritating noises of varying levels of loudness and frequency patterns. The later recall of a loud noise was improved by adding a period of diminishing volume.

The overall amount of pleasantness or unpleasantness was assessed post-study. The experience of 16 seconds at 78 dB was rated worse than the same experience followed by 8 extra seconds at 66 dB.

Finn et al. (2010) explored the memories of discomfort in an effortful learning experience and the impact this evaluation has on prospective study choices. The design of these two studies was similar to the cold submersion studies as well. Researchers used an especially challenging learning experience instead of a painful experience.

A strong effortful study episode extended by a moderate study period was preferred to a shorter, not extended interval, despite improved test scores post-assessment.

Peak-End Theory of Pleasure

Researchers have studied the peak-end effect in painful experiences, yet also have explored the effect on pleasurable experiences. Studies suggest that our memories of hedonic or pleasurable experiences are also inaccurate.

Kahneman explores how this relates to hedonic psychology and happiness metrics in his 2011 book Thinking Fast and Slow. A notable insight is that the experience of pleasure or pain at the moment becomes replaced by the memory of that pleasure or pain (how it is perceived after event upon recall).

Diener, Wirtz, and Oishi (2001) conducted studies to explore the impact of peak-end theory on positive experiences. In their study, participants rated a wonderful life that ended suddenly as being better than one with additional, yet mildly pleasant years. Researches referred to this as the James Dean Effect.

Fredrickson and Kahneman have also pursued studies on pleasurable experiences. In their study (1993), participants viewed a series of videos that ranged in pleasantness and duration. Research indicated that individuals disregarded the duration of an affective episode when making their retrospective assessments. They heavily relied on limited moments in the episode to form their conclusion.

Studies have also explored the impact of peak-end theory on consumer behavior. Television commercials that create positive feelings are rated more highly by viewers if there are peaks of intensity and end on a positive note. (Baumgartner, Sujan, & Padgett, 1997).

Researchers Do et. al (2008) applied the peak-end concepts to material items. They explored the impact of positivity and timing on the post-event assessments of material goods. Their studies confirm that the peak-end rule applies to both material goods and pain.

They discovered that children were more pleased after receiving a chocolate treat alone when they received the same chocolate treat followed by a mildly enjoyable piece of gum. Children preferred only the chocolate bar, even though it was one vs two treats because their retrospective assessments were most impacted by the end of the experience. Providing the gum after the treat caused the experience as a whole to be less pleasurable for them.

Do et al (2008) also explored the peak-end effect of receiving gifts. Participants were given gifts and asked to rate how happy the gifts made them. Researchers hypothesized that participants would be less happy with a highly desirable gift if it was followed by a less desirable gift.

Their method included rewarding college students part of a fundraising project by allowing them to select a DVD from one or two lists. Participants could select from an “A list” of top-rated movies and the other half selected from a “B list” of less favorable films.

The participants who ended their experience by receiving the less desirable gift last were less happy. The authors reported, “Two positives are given a lower rating than a single positive if the second item is less positive.”

Research supports that an event with a pleasurable peak at the end will be remembered positively. Studies have shown that adding a positive end to a pleasant exercise session will impact the decision to repeat the exercise (Soundarapandian 2009). In the discussion, it is recommended for exercise activities should end on a high note.

8 Videos Worth Watching

1. Peak End Effects – Part of a series on cognitive biases

Laurie Santos (Yale University) explains why our memories of good and bad events are biased. She describes how our post-event evaluations are impacted by the peak-end effect.

2. Daniel Kahneman TEDX Talk

The Riddle of Experience vs Memory

3. Daniel Kahneman Talk at Google YouTube Video

4. Video Review for Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman YouTube Video

5. What is PEAK-END RULE? What does PEAK-END RULE mean? PEAK-END RULE meaning & explanation

The Audiopedia

6. What is Duration Neglect?

The Audiopedia

7. Daniel Kahneman: The Experiencing Self vs. The Remembering Self – [ON BOOKS EPISODE #12]

OnBooks Podcast YouTube Video

8. Adam Fraser 7 minute summary of peak-end theory

A Take-Home Message

We can use this insight into our cognitive biases to our advantage. It provides data for us to impact our experiences in the future. Implications from research suggest that we can construct peak points or highlights in our experiences in order to enhance pleasure.

We can leverage the trick of peak-end theory to help craft how our memories are formed. It would make sense that fostering positive memories would be appealing.

Consider the following tips to leverage your memory-making:

- Attempt to end your experiences on a high note. Find something positive to focus on at the end of an experience.

- Try not to dwell on the negative elements of a situation. If you have to wait in line, consider how grateful you are once you get to the front of the line. If you experience poor service at a restaurant, focus on how good your meal was.

- Try not to let the minor discomforts or annoyances color your recollection of the whole experience.

- Many experiences can be reframed at the moment to create more positive and intense emotion.

By hacking the peak-end theory, we can empower ourselves to improve happiness, wellbeing, and our state of mind. We hope you have enjoyed this article and can find ways to harness the value of behavioral science!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Baumgartner, H., Sujan, M., & Padgett, D. (1997). Patterns of affective reactions to advertisements: The integration of moment-to-moment responses into overall judgments. Journal of Marketing Research, 32, 219-232.

- Chajut, E., Caspi, A., Chen, R., Hod, M., & Ariely, D. (2014). In pain thou shalt bring forth children: The peak-and-end rule in recall of labor pain. Psychological Science, 25, 2266–2271.

- Cockburn, A., Quinn, P., & Gutwin, C. (2015, April). Examining the peak-end effects of subjective experience. In Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 357-366).

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., & Oishi, S. (2001). End effects of rated life quality: The James Dean effect. Psychological Science, 12, 124-128.

- Do, A.M, Rupert, ,V., & Wolford, G. (2008). Evaluations of Pleasurable Experiences: The Peak-End Rule. Psychonomic Bulletin & review, Volume 15 (1), 96-98.

- Egan Brad, L. C., Lakshminarayanan, V. R., Jordan, M. R., Phillips, W. C., & Santos, L. R. (2016). The evolution and development of peak-end effects for past and prospective experiences. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 9(1), 1-13.

- Finn, B. (2010). Ending on a high note: Adding a better end to effortful study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36, 1548–1553.

- Finn, B., & Miele, D. B. (2016). Hitting a high note on math tests: Remembered success influences test preferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 42 (1), 17-38.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Extracting meaning from past affective experiences: The importance of peaks, ends, and specific emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 14, 577-606.

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Kahneman, D. (1993). Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 65, 44-55.

- Healy, A. & Lenz, G. S. (2014), Substituting the end for the whole: Why voters respond primarily to the election-year economy. American Journal of Political Science, 58, 31– 47.

- Hoogerheide, V., & Paas, F. (2012). Remembered utility of unpleasant and pleasant learning experiences: Is all well that ends well? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(6), 887-894. Kahneman, D.

- Hoogerheide, V., Vink, M., Finn, B., Raes, A.N., & Paas, F. (2018) How to bring the news….peak-end effects in children’s affective responses to peer assessments of their social behavior. Journal of Cognition and Emotion, Volume 32 Issue 5.

- Kahneman, D. (1999) Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kahneman, D., Fredrickson, B. L., Schreiber, C. A., & Redelmeier, D. A. (1993). When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science, 4, 401-405.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1999). Evaluation by moments: Past and future. In D. Kahneman & A. Tversky (Eds.), Choices, values, and frames (pp. 2-23). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Miron-Shatz, T. (2009). Evaluating multi-episode events: Boundary conditions for the peak-end rule. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 9, 206–213.

- Miron-Schatz, T., Stony S. & Kahneman D. (2009). Memories of Yesterday’s Emotions: Does the Valence of Experience Affect the Memory-Experience Gap? Emotion, Vol. 9, No. 6, 885– 891

- Peterson, D.A. & Kozhokar, D. (2017). Peak-End Effects for Subjective Mental Workload Ratings. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 2017 Annual Meeting.

- Redelmeier, D. A., & Kahneman, D. (1996). Patients’ memories of painful medical treatments: Real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures. Pain, 66, 3-8.

- Redelmeier, Donald A; Katz, Joel; Kahneman, Daniel (2003). Memories of colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Pain. 104 (1-2): 187–194.

- Schreiber, C. A., & Kahneman, D. (2000). Determinants of the remembered utility of aversive sounds. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 129, 27-42.

- Schwartz, Barry. The Paradox of Choice – Why More Is Less. New York: Harper Perennial, 2004.

- Varey, C. & Kahneman, D (July/September 1992). Experiences extended across time: Evaluation of moments and episodes. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Volume 5, Issue 3.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (41)

- Coaching & Application (49)

- Compassion (27)

- Counseling (46)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (16)

- Grief & Bereavement (19)

- Happiness & SWB (35)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (21)

- Mindfulness (42)

- Motivation & Goals (42)

- Optimism & Mindset (33)

- Positive CBT (24)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (41)

- Positive Emotions (28)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (38)

- Relationships (31)

- Resilience & Coping (33)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Software & Apps (23)

- Strengths & Virtues (28)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (27)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (30)

- Types of Therapy (53)

What our readers think

Thanks, Karen, for capturing the literature so beautifully. It really has been a fascinating journey for me in terms of measuring happiness. Thanks for citing my work! Talya Miron-Shatz, PhD.

Loved this article, it makes total sense of how do we handle relationships in our life and the impact they leave on the way we lead our lives..Thanks Karel, looking forward to many more.