The Science & Psychology Of Goal-Setting 101

Imagine yourself going to work aimlessly every day, talking to others without a reason, working out just because you have to, and not having any aspirations for yourself or those around you.

Imagine yourself going to work aimlessly every day, talking to others without a reason, working out just because you have to, and not having any aspirations for yourself or those around you.

How would you feel?

Goal-setting in psychology is an essential tool for self-motivation and self-drivenness – both at personal and professional levels. It gives meaning to our actions and the purpose of achieving something higher.

By setting goals, we get a roadmap of where we are heading to and what is the right way that would lead us there. It is a plan that holds us in perspective – the more effectively we make the plan, the better are our chances of achieving what we aim to. Rick McDaniel (2015) had quoted,

“Goal-setters see future possibilities and the big picture.”

Setting goals are linked with higher motivation, self-esteem, self-confidence, and autonomy (Locke & Latham, 2006), and research has established a strong connection between goal-setting and success (Matthews, 2015).

This post is all about understanding the benefits of goal-setting and implementing that knowledge in our day-to-day lives. In the following sections, we will take an in-depth look into how goal-setting influences the mind to change for the better, and contribute to making smarter decisions for ourselves.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

- What is Goal Setting? A Psychological Definition

- The Psychology of Goal Setting

- How is Goal Setting Used in Psychology?

- Goal Setting and Positive Psychology

- A Look at Goal Setting Theory

- Psychological Studies and Research on Goal Setting

- 3 Interesting Research Findings

- 3 Goal Setting Case Studies

- Goal Setting and the Brain: A Look at Neuroscience

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is Goal Setting? A Psychological Definition

Goal setting in psychology refers to a successful plan of action that we set for ourselves. It guides us to choose the right moves, at the right time, and in the right way. In a study conducted on working professionals, Edwin A. Locke, a pioneer in the field of goal-setting, found that individuals who had highly ambitious goals had a better performance and output rate than those who didn’t (Locke, 1996).

Frank L. Smoll, a Ph.D. and a working psychologist at the University of Washington emphasized on three essential features of goal-setting, which he called the A-B-C of goals. Although his studies focused more on athletic and sports-oriented goal-setting, the findings held for peak performers across all professions.

ABC of Goals

Smoll said that effective goals are ones that are:

- A – Achievable

- B – Believable

- C – Committed

Goal-setting as a psychological tool for increasing productivity involves five rules or criterion, known as the S-M-A-R-T rule. George T. Doran coined this rule in 1981 in a management research paper of the Washington Power Company and it is by far one of the most popular propositions of the psychology of goals.

SMART Goals

S-M-A-R-T goals stand for:

- S (Specific) – They target a particular area of functioning and focus on building it.

- M (Measurable) -The results can be gauged quantitatively or at least indicated by some qualitative attributes. This helps in monitoring the progress after executing the plans.

- A (Attainable/Achievable) – The goals are targeted to suitable people and are individualized. They take into account the fact that no single rule suits all, and are flexible in that regard.

- R (Realistic) – They are practical and planned in a way that would be easy to implement in real life. The purpose of a smart goal is not just providing the plan, but also helping the person execute it.

- T (Time-bound) – An element of time makes the goal more focused. It also provides a time frame about task achievement.

SmartER Goals

While this was the golden rule of goal-setting, researchers have also added two more constituents to it, and call it the S-M-A-R-T-E-R rule.

The adjacents include:

- E (Evaluative/ethical) – The interventions and execution follow professional and personal ethics.

- R (Rewarding) – The end-results of the goal-setting comes with a positive reward and brings a feeling of accomplishment to the user.

Cecil Alec Mace was the first person to carry out empirical studies on goal-setting (Carson, Carson, & Heady, 1994). His work emphasized the importance of willingness to work and indicated that the right plans could be a sure shot predictor of professional success (Mace, 1935).

Locke continued his research on goal-setting from there, and in the 1960s, came up with the explanation of the usefulness of goals for a happier and more content life (Locke, 2002).

Today, planning goals is an essential part of educational and organizational psychology. Many organizations encourage employees to undergo screening for goal-setting and use the resources to measure their productivity at work (Kleingeld, van Mierlo, & Arends, 2011).

The Psychology Of Goal Setting

Goals play a dominant role in shaping the way we see ourselves and others. A person who is focused and goal-oriented is likely to have a more positive approach towards life and perceive failures as temporary setbacks, rather than personal shortcomings.

Tony Robbins, a world-famous motivational speaker, and coach had said that “Setting goals is the first step from turning the invisible to visible.”

Studies have shown that when we train our mind to think about what we want in life and work towards reaching it, the brain automatically rewires itself to acquire the ideal self-image and makes it an essential part of our identity. If we achieve the goal, we achieve fulfillment, and if we don’t, our brain keeps nudging us until we achieve it.

Psychologists and mental health researchers associate goals with a higher predictability of success, the reasons being:

Goals involve values

Effective goals base themselves on high values and ethics. Just like the S-M-A-R-T-E-R goals, they guide the person to understand his core values before embarking upon setting goals for success. Studies have shown that the more we align our core values and principles, the more likely we are to benefit from our goal plans (Erez, 1986).

Goals bind us to reality

A practical goal plan calls for a reality check. We become aware of our strengths and weaknesses and choose actions that are in line with our potentials. For example, a good orator should set goals to flourish as a speaker, while an expressive writer must aim to succeed as an author.

Realizing our abilities and accepting them is a vital aspect of goal-setting as it makes room for introspection and helps in setting realistic expectations from ourselves.

Goals call for self-evaluation

Successful accomplishment of goals is a clear indicator of our success. We don’t need validation from others once we have achieved the goals we set for ourselves. The scope of self-evaluation boosts self-confidence, efficacy, self-reliance, and gives us the motivation to continue setting practical goals in all subsequent stages of life.

4 Steps To Successful Goal-Setting

1. Make a plan

The first step to successful goal-setting is a brilliant plan.

Chalking out our goals by our strengths, aspirations, and affinities is an excellent way to build a working program. The plan makes habit formation easier – we know where to focus and how to implement the actions.

2. Explore resources

The more we educate ourselves about goal-setting and its benefits, the easier it becomes for us to stick to it. We can start building our knowledge base by taking expert advice, talking to supervisors at the workplace, or participating in self-assessments.

Assessments and interactions help us realize the knowledge gaps and educate ourselves in the areas concerned.

3. Be accountable

A crucial requisite of goal-setting is accountability. We tend to perform better when someone is watching over us, for example, it is easier to cheat on a diet or skip the gym when we are doing it alone.

But the moment we pair up with others or have a trainer to guide us through the process, there are increased chances of us sticking to the goals and succeeding in them.

4. Use rewards and feedbacks

Rewarding ourselves for our efforts and achievements makes sticking to the plan more comfortable for us. Managers who regularly provide feedback to their employees and teammates have better performance in their teams than ones who don’t interact with employees about their progress.

How is Goal Setting Used in Psychology?

Setting goals gives our mind the power to imagine our ideal future, the way we want to see ourselves in years to come. By gaining insight into our wants and needs, we become aware of our reality and can set reasonable expectations.

Goal-setting impacts both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and this is why most successful athletes and business professionals rely on a sound plan of action before diving into any work.

There are many instances of how goal-setting is effectively used as a psychological intervention.

For example:

- Popular therapeutic practices like the CBT or Anger Management often use weekly goal planners or charts to record the progress of the clients and help them keep track of the exercises they are supposed to practice at home. Even in child therapies, counselors often use mood charts or set weekly exercises for the kid, and provide positive reinforcements to the child on accomplishing them.

- Almost all educational institutions today agree that setting clear goals makes it easier for the students to realize their strengths and work on building them. It boosts their self-confidence and lets them identify the broader targets in life.

- Goal-setting as a personal habit is also beneficial to hold ourselves in perspective. Personal goal-setting may be as simple as maintaining a daily to-do list or planning our career moves beforehand. As we have a clear vision of the end-goals, it becomes easier for us to advance towards them.

Types of goals

There are three main types of goals in psychology:

- The Process Goals

These are the ones involving the execution of plans. For example, going to the gym in the morning or taking the health supplements on time, and repeating the same action every day is a process goal. The focus is to form the habit that will ultimately lead to achievement. - The Performance Goals

These goals help in tracking progress and give us a reason for continuing the hard work. For example, studying for no less than 6 hours a day or working out for at least 30 minutes per day can help us in quantifying our efforts and measuring the progress. - The Outcome Goals

Outcome goals are the successful implementations of process and performance goals. They keep us in perspective and help to stay focused on the bigger picture. Examples of outcome goals may include winning a sport, losing the desired amount of weight, or scoring a top rank in school.

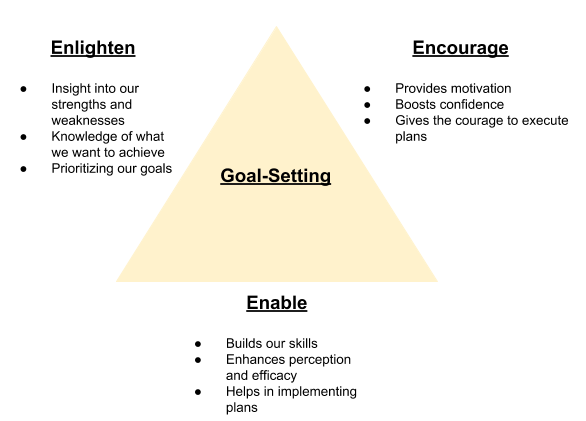

The E-E-E Model Of Goal-Setting

The E-E-E Model of goal-setting was mentioned in a journal published by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2017). It is a person-centered approach that describes the way a successful roadmap contributes to bringing about the change.

Author Nowack (2017). stated that goal-setting ensures success by serving three purposes:

- Enlightening Us

Providing meaningful insight into our abilities and weaknesses, and by helping us prioritize our goals depending on our needs. - Encouraging Us

It provides the motivation and courage to implement the goals and execute the plans efficiently. - Enabling Us

Goal-setting enables us to achieve the balance between our real and ideal self. By implementing the goals and succeeding from it, we regain self-confidence, social support, and can evaluate our achievements.

Goal Setting and Positive Psychology

Goals direct our actions and open us to a host of new possibilities. They help us stick to the relevant activities and get rid of what is irrelevant for goal-satisfaction.

Martin Seligman’s research and findings on positive psychology aimed to shift the focus of psychology from problems to solutions. His works emphasized on interventions that would increase managerial productivity and help leaders enhance their performance holistically (Luthans, 2002).

Positive psychology incorporates the principles of goal-setting in several ways:

- It commits to a specific set of actions for goal-setting.

- It considers individual ethics and core values before setting goals.

- It aligns actions to individual capacities and character strengths.

- It has space for introspection and insight into one’s thoughts, emotions, and perceptions.

- It helps in setting realistic goals and expectations, thereby aiming to boost self-confidence and energy by task accomplishments.

Professor Gary P. Latham (University of Toronto) emphasized the role of positive psychology and the interconnection of it to goal-setting in his groundbreaking work on life goals and psychology. He mentioned that optimistic people have a strong sense of self, which helps them derive the motivation to set goals and extend them for self-improvement.

Positive psychology, according to Latham, intersects with goal-setting in the sense that it calls for building self-efficacy and create a sense of mastery over our internal and external environments.

Author Doug Smith (1999), in his famous book “Make Success Measurable! A Mindbook For Setting Goals And Taking Actions” mentioned that successful goal-setting mainly involves asking three questions to the self:

- How important is the goal for us?

- How confident are we about reaching and accomplishing the goal?

- How consistent is the goal with our core values and beliefs?

Smith said that successful leaders and management professionals use this systematic approach when striving for goal accomplishments and use threads of positive psychology such as optimism, thought replacement, strength, and resilience.

The emerging field of positive psychology provides a stronger base for effective goal-setting and management.

A Look At Goal Setting Theory

Locke’s prime concern was to establish the power of setting accurate and measurable goals.

He believed that rather than focusing on general outcomes, professional goal-setting and management should focus on meticulousness of the tasks and address specific goals for each area of accomplishment. The goal-setting theory Locke designed, set an impetus to increased productivity and achievement.

Principles Of Locke’s Theory

Locke’s theory of goal-setting is the roadmap to today’s workplace motivation and skills to build it. In his argument, he mentioned that effective goal-setting directly contributes to productivity and increases employee satisfaction at all professional levels.

Locke believed that there are five key principles of goal-setting:

- Clarity – How specific and comprehensive the goal is.

- Challenge – How difficult the goal is and the degree to which it requires us to extend our abilities.

- Commitment – How dedicated we are to reach the goal and what value it renders to us.

- Feedback – How our achievements are perceived and recognized by others. Positive feedback increases satisfaction after achieving the target.

- Complexity – The difficulty of the tasks that we need to accomplish for reaching the ultimate goal.

Core Concepts Of Goal-Setting Theory

Locke said that there are four core components of a goal that makes it useful. These are the key aspects that we should keep in mind before committing to a plan.

1. Difficulty

Difficult goals imply more significant achievements. Easy and comfortable goals are seldom productive, as we don’t have to exploit much of our abilities to achieve them.

Although while selecting a target, we may tend to shun away from choosing the harder ones, difficult goals are undoubtedly more motivating, energizing, and satisfying after accomplishment.

2. Specificity

Specific goals imply more certain task regulation. Before setting a goal plan, we must be clear to ourselves about the outcomes and which part of our personal or professional lives will the target achievement improve.

Having a vision of the result strengthens our intentions and helps to sustain focus.

3. Reward reminders

Locke emphasized the importance of following inspirational musings and motivational speeches for goal accomplishments. He said that the human mind is too used to getting reminders from its internal or external environment when it faces a lack of something.

For example, lack of food or water is triggered by feelings of hunger and thirst that motivates us to achieve the equilibrium again. But with professional targets or life goals, it is not absurd to lose motivation unless we keep reminding ourselves of why we should attain it.

4. Goal efficacy

The success of Locke’s theory owes to its cut-throat practical approach. While mentioning about optimism bias in his opinion, Locke said that we often tend to select goals that excite us temporarily.

For example, we may choose a profession by getting lured about the financial benefits of it, failing to notice the hard work that we will need to put in for enjoying the benefits. As a result, we are likely to fail motivation and lose commitment after delving into the reality of the work.

Thus, before setting goals, it is vital that we choose only the ones that are truly rewarding to us, no matter how much we need to push ourselves to achieve it.

Psychological Studies And Research On Goal Setting

Goal-setting is an area in psychology whose roots lie in scientific data and empirical evidence. It is a flexible theory which is open to modifications according to the changing times, and yet serve the purpose of:

- Maximizing success.

- Minimizing failures and disappointments.

- Optimizing personal abilities (Latham & Locke, 2007)

A study on the effects of goal-setting on athletic rehabilitation and training revealed that groups that followed a solid plan of action were more prepared, had higher self-efficacy, and were more organized in their approach (Evans & Hardy, 2002).

The experimental population had three groups, only one of which received the goal-setting intervention. Post-experimental measures showed there was a significant difference in the levels of spirit and motivation among the group that received the goal-setting interventions and the other two groups.

George Wilson’s study on “Value-Centred Approach To Goal-Setting And Action Planning” also put forth some groundbreaking revelations. He based the survey of the seven practices Seligman had mentioned in his research on positive psychology and goal-setting (Kerns, 2005).

Wilson called them ‘key takeaways’ and urged organizations to consider these seven highlights while setting up their goal-management programs:

1. Values Commitment

Wilson coined five core values using a value-based checklist. His study showed that when goal-setting focus on the core values, it increased the likelihood of achieving success from the target plan.

The five core values he mentioned were – integrity, responsibility, fairness, hope, and achievement.

2. Goals and Values Alignment

Wilson set the goals in his study based on the core values, such that each goal satisfies at least one or more of the purposes mentioned above. Results showed that the goals which were associated with the values gave more satisfaction to the participants than the ones which were not.

3. Character Strengths and Actions

Seligman’s findings strongly stated that goal-setting and achievements must take into account the character strengths of the individual.

In the absence of character alignment, there will remain a chance of selecting actions that are too easy or way too complicated for the person to accomplish. Wilson extended his study based on this finding and used the Values in Action (VIA) inventory to rule out the strengths and abilities of the participants before choosing the right goals for them.

4. Self-confidence

Positive psychology research on goal-setting spoke about how confidence and goals tend to complement each other. Wilson’s study incorporated regular self-checks for one year post the survey to examine the level of self-confidence of the respondents and determine its influences on their achievements.

5. Persistence

Frequent investigations in the form of self-assessments, interviews, or feedbacks are essential in gauging whether the participants are consistent with their targets. Seligman and his colleagues considered perseverance and consistency hugely critical for ensuring successful execution of the target plans.

6. Realistic outlook

The importance of setting realistic expectations cannot be stressed enough when talking of successful goal-setting. Wilson’s research on goal-setting encouraged participants to take the Seligman Optimism Test for gaining insight into the self-perceptions and followed three approaches to maintain an optimistic perspective in the participants:

- Separating facts from negative thoughts and ruminations.

- Encouraging positive self-talk among the groups.

- Using at least one positive statement in each of the weekly reports where he mentioned the target plans and goals associated with it.

7. Self-resilience

Wilson suggested that measuring the Resilience Quotient (RQ) of participants before assigning goals to them is a great idea for optimizing success and promoting happiness (Kerns, 2005). On administering resilience scales to the respondents, the goal-setting and task assignment be came more accessible and guaranteed better outcomes.

3 Interesting Research Findings

There are even more interesting studies, and we share three interesting findings here.

1. A Study On The Interrelationships Among Employee Participation, Individual Differences, And Goal-Setting

Yukl and Latham published this research in 1978 where they explored the interconnections between goal-setting and individual personality factors.

For 10 weeks, 41 participants received goal plans that were either set by supervisors or chosen by the participants themselves, and the results revealed that:

- Participants with difficult goals achieved greater success than others.

- Participants with higher self-esteem did better on task accomplishments.

- Participants with a greater understanding of why the goal was necessary for them had more chances of being successful with the target plans.

2. Dr. Gail Matthews’ (2015) Study On Goal-Setting

A study conducted by Dr. Gail Matthews at Dominican University sought to find evidence for claims coming out of Harvard Business School that well-planned and well-written goals impact students’ performance and achievements.

In this study, 267 participants were recruited from businesses and professional networking groups to take part. These participants were then divided into five groups:

- The first group set no goals and had no concrete plans.

- The second group set goals but did not prepare a plan to execute them.

- The third group prepared well-defined goals and plans of action to achieve them.

- The fourth group prepared well-defined goals and plans of action, then sent these to a supportive friend.

- The fifth group prepared well-defined goals and plans of action, then sent these to a supportive friend, together with weekly progress reports.

Results revealed that the fifth group, who had their goals written with concrete plans of action and drew on the support of a friend to hold them accountable, accomplished significantly more than all the other groups. This study serves to highlight the benefits of writing down goals and action plans, as well as the benefits of public commitment and accountability as drivers of goal achievement and success in life.

3. A Study On Success And Goals

This was a small enterprise-oriented study that explored how goal-setting and entrepreneurial qualities affected the productivity of the employees and the overall success of the organization. Results indicated the importance of marketing abilities of the organizational head to be a significant influence in the company’s goal-setting plans (Ioniţă, 2013).

3 Goal Setting Case Studies

1. A Case Study By Emily van Sonnenberg

Emily VanSonnenberg (2011), a psychologist specializing in positive psychology and happiness coach, presented her case study on undergraduates to explain the importance of having goals in life.

The target group of her research was young adults who came from a non-psychology background. She mentioned about starting each session with positive interventions like brief meditation, mindfulness, and task planning, and urged her subjects to journal the tidbits of these positive interventions daily.

Over a while, Emily found that individuals who kept a detailed record of their daily goals and planned their tasks accordingly were more productive, less bored, and showed signs of higher self-contentment than others.

She further mentioned that asking questions to the self like “What do you intend to do today?”, or “What do you want to achieve in life?”, etc., can clarify our motivations and help in setting our goals more effectively.

Although her study targeted only a particular age-group, the findings are valid for people across different ages and professional backgrounds.

2. A Goal-Setting Case Study By Redmond

This case study was based on professional goal-setting and the use of S-M-A-R-T-E-R goals in achieving success (Redmond, 2011). Following the critical findings of the book ‘Contemporary Management’ by Jones and George, researcher Brian F. Redmond suggested the participants create smart goals for them and report their progress to the supervisors regularly (Redmond, 2011).

One participant of the study, John, received a Professional Development Plan (PDP) intending to build his potentials and maximize his achievements. The PDP allowed him to evaluate his character strengths closely and identify the areas that needed improvement.

John set his goals based on his powers and kept reporting his progress and task accomplishments to his supervisors, who kept extending and modifying the targets based on whether or not they were achieved.

This individualized case study asserted the role of setting smart goals in achieving success and building personal skills.

3. Goal-Setting Case Study By Hardin

Deedra Hardin had published a valuable collection of fascinating case studies on goal-setting and success at different organizational levels.

Out of the series of studies, one case research on the effectiveness of goal-setting in the military service is noteworthy to mention here (Hardin, 2013).

A group leader of a commander team, who was in charge of training over a hundred soldiers, had the responsibility of ensuring that his team members met the physical, systematic, and operational requirements of the top in their field. The goals that the commander set for his army focused a lot on physical fitness and set smart goals that would help his team achieve the same.

Hardin said that the reason why the commander succeeded in creating quick goals for his teams was his intuition and insight into the exact requirements for the team.

Extending the study from there, authors of the research stated that for successfully building a goal plan that can guarantee satisfaction for both the administrator and the respondent, it is vital to understand what the team precisely needs and how the goals can help them achieve so.

Furthermore, the study also indicated that goal-setting could only become successful after the results were reviewed and monitored by the authorities or the participants themselves (Hollenbeck & Klein, 1987).

Goal Setting and the Brain: A Look at Neuroscience

Goal-setting gives a boost to our Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) which makes us readily act on it (Granot, Stern, & Balcetis, 2017). When the goal is tricky and yet achievable, the SBP gets an enhanced spike that increases our zeal to act and achieve it.

Impossible or challenging goals, or the ones that make us question our abilities, are linked with low systolic thrust and they do not provide the spike for ready action. Extensive studies have shown how neural connections and the brain activities pump up our motivation to set and achieve goals.

For example, the Medial Prefrontal Cortex (MPFC) deals with the present orientation of the goal-setting process. The MPFC activation allows us to think about what we need to do right now to achieve our goals, and we set the targets accordingly.

If the goal seems too distant or is too future-oriented, the MPFC activation lowers significantly which is why we may lose interest in sticking to the goals or lose the vision of what might be the best ways to achieve them.

Usually, goals are the incidents that have not yet happened to us, but we want to make them happen. And since they cannot occur on their own, we follow a set of rules or a plan to ensure achievement (Balcetis & Dunning, 2010).

The sense of struggle and power testing that involves the goal-setting process is what makes it so engaging to us. For example, a primary drive or intrinsic motivation that forces us to do well on a new or challenging assignment is the ability to demonstrate and validate our skills (McClelland, 1985).

The underlying neurochemical changes that cause this motivation to keep burning is therefore vital to understand before we embark on setting the goals.

RAS And Goal Setting

Reticular Activating System (RAS) is a part of the brain that plays a crucial role in regulating our goal-setting actions. The RAS is a cluster of cells located at the base of the brain that processes all the information and sensory channels related to the things that need our attention right now.

An exciting fact about RAS activation is that it gives us signs. For example, a person whose goal is to start a family, is likely to see more couples and families around him.

This happens because of RAS activation. The RAS is aware that this is what the person is paying attention to at this very moment, and hence he chooses to register only the information related to it.

Before deciding to start a family, the RAS would naturally have filtered out any such information. The person may have seen so many couples walking past him earlier, but never really paid attention to them, until the time he decided to get married himself (Alvarez & Emory, 2006).

The reticular activation functions in two ways when it comes to goal-setting:

1. Writing goals

RAS gets activated by the simple act of putting our goals in pen and paper. Seeing our aims written in clear words before us, feeling the touch of the pen, or engaging in the thinking process of writing the targets trigger the RAS functions and ensures that we go for it.

2. Planning goals

The art of imagination is essential when it comes to goal-setting. Studies have shown that people who have the power to visualize their goals before setting their actions have a higher activation at the brain level.

Repeatedly imagining success and reminding ourselves of our targets maintains a steady stimulation in the RAS and promotes effective goal-setting (Berkman & Lieberman, 2009).

The RAS activation helps in focusing the mind to attend to only those pieces of information that are related to the goals we seek to achieve.

Neurologists working on the science of goal-setting have proved that the brain cannot distinguish between reality and imagined reality. So, when we give ourselves a picture of the goal we want to achieve, the mind starts believing it to be real.

Eventually, the brain begins driving us to take actions for making the state and hence, the goal-setting becomes a success (Berkman, 2018).

A Take-Home Message

As the famous saying goes, “Begin with the end in mind.” The most crucial aspect of goal-setting is to build an effective plan.

If we set goals by our character strengths, core values, level of motivation, and pledge on sticking to the plan until we reach the aim, there is no way that we won’t get there.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free.

- Alvarez, J. A., & Emory, E. (2006). Executive function and the frontal lobes: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology Review, 16(1), 17-42.

- American Psychological Association. (2017, September 27). Beyond goal setting to goal flourishing. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pubs/highlights/spotlight/issue-101

- Balcetis, E., & Dunning, D. (2010). Wishful seeing: More desired objects are seen as closer. Psychological Science, 21(1), 147-152.

- Berkman, E. T. (2018). The neuroscience of goals and behavior change. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 70(1), 28-44.

- Berkman, E. T., & Lieberman, M. D. (2009). Using neuroscience to broaden emotion regulation: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 475-493.

- Carson, P. P., Carson, K. D., & Heady, R. B. (1994). Cecil Alec Mace: The man who discovered goal-setting. International Journal of Public Administration, 17(9), 1679-1708.

- Doran, G. T. (1981). There’sa SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35-36.

- Erez, M. (1986). The congruence of goal-setting strategies with socio-cultural values and its effect on performance. Journal of Management, 12(4), 585-592.

- Evans, L., & Hardy, L. (2002). Injury rehabilitation: A goal-setting intervention study. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 73(3), 310-319.

- Granot, Y., Balcetis, E., & Stern, C. (2017). Zip code of conduct: Crime rate affects legal punishment of police. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 3(2), 176-186.

- Hardin, D. L. (2013). Case studies using goal-setting theory. Retrieved from https://wikispaces.psu.edu/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=118882898

- Hollenbeck, J. R., & Klein, H. J. (1987). Goal commitment and the goal-setting process: Problems, prospects, and proposals for future research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(2), 212–220.

- Ioniţă, D. (2013). Success and goals: An exploratory research in small enterprises. Procedia Economics and Finance, 6, 503-511.

- Kerns, C. D. (2005). The positive psychology approach to goal management. Graziadio Business Report, 8(3).

- Kleingeld, A., van Mierlo, H., & Arends, L. (2011). The effect of goal setting on group performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1289-1304.

- Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2007). New developments in and directions for goal-setting research. European Psychologist, 12(4), 290-300.

- Locke, E. A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 3(2), 157-189.

- Locke, E. A. (1996). Motivation through conscious goal setting. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 5(2), 117-124.

- Locke, E. A. (2002). Setting goals for life and happiness. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 299–312). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265-268.

- Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 695-706.

- Mace, C. A. (1935). Incentives: Some experimental studies (Report No. 72). London, UK: Industrial Health Research Board.

- Matthews, G. (2015). Goal research summary. Paper presented at the 9th Annual International Conference of the Psychology Research Unit of Athens Institute for Education and Research (ATINER), Athens, Greece.

- McClelland, D. C. (1985). How motives, skills, and values determine what people do. American Psychologist, 40(7), 812-825.

- McDaniel, R. (2015, June 30). Goal setter or problem solver? HuffPost. Retrieved from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/goal-setter-or-problem-so_b_7543084

- Nowack, K. (2017). Facilitating successful behavior change: Beyond goal setting to goal flourishing. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(3), 153-171.

- Redmond, B. F. (2011). Goal setting case study. Retrieved from https://wikispaces.psu.edu/display/PSYCH484/Goal+Setting+Case+Study

- Smith, D. K. (1999). Make success measurable! A mindbook-workbook for setting goals and taking action. New York, NY: Wiley.

- VanSonnenberg, E. (2011, January 3). Ready, set, goals! Positive Psychology News. Retrieved from https://positivepsychologynews.com/news/emily-vansonnenberg/2011010315821

- Yukl, G. A., & Latham, G. P. (1978). Interrelationships among employee participation, individual differences, goal difficulty, goal acceptance, goal instrumentality, and performance. Personnel Psychology, 31(2), 305-323.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (41)

- Coaching & Application (49)

- Compassion (27)

- Counseling (46)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (16)

- Grief & Bereavement (19)

- Happiness & SWB (35)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (21)

- Mindfulness (42)

- Motivation & Goals (42)

- Optimism & Mindset (33)

- Positive CBT (24)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (41)

- Positive Emotions (28)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (38)

- Relationships (31)

- Resilience & Coping (33)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Software & Apps (23)

- Strengths & Virtues (28)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (27)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (30)

- Types of Therapy (53)

What our readers think

Awesome article, very informative reasearch behind it. This is gonna be helpful to set my goals in a better way. Thankyou.

Great article. Thanks so much.