What is Post-Traumatic Growth? (+ Inventory & Scale)

As they say, trauma is a nightmare that comes while we are awake. Not only is it difficult to overcome trauma, but it also takes tremendous effort and perseverance to do so.

As they say, trauma is a nightmare that comes while we are awake. Not only is it difficult to overcome trauma, but it also takes tremendous effort and perseverance to do so.

But suffering has transformative power. Be that in religion, poetry, philosophy, or literature – the general understanding of how pain can be beneficial is not a new concept altogether.

Positive psychology has embraced this process of thriving and calls it Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG) – or the self-improvement one undergoes after experiencing life challenges.

We all hear about stress and its inevitability, yet succumb to the displeasure when it strikes us. While resilience may help to withstand the pain to some extent, PTG allows us to grasp the knowledge of using the pain to change our lives for the better.

In the following sections, we will delve a little deeper than what we have known so far about trauma and coping. With evidence-backed examples, this article will help in understanding the essentials of PTG and how to apply the same in our lives. Here you can access more practical Post-traumatic tools, worksheets, and techniques.

Before you continue reading, we thought you might like to download our three Grief Exercises [PDF] for free. These science-based tools will help you move yourself or others through grief in a compassionate way.

This Article Contains:

- What is Post-Traumatic Growth? A Definition

- A Look at the Psychology and Theory

- Research and Studies

- A Look at the Work of Tedeschi and Calhoun

- 5 Examples of Post-Traumatic Growth

- PTG and Positive Psychology

- Post Traumatic Growth and Resilience

- What Common Forms of Therapy are used for PTG?

- A Look at Post-Traumatic Growth Syndrome

- A Look at the Possible Symptoms of PTG

- What is the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory?

- Where Can I Find the Scale?

- Common Criticisms of PTG

- 5 Recommended Ted Talks and YouTube Videos

- 4 Books on the Topic

- 10 Quotes

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What is Post-Traumatic Growth? A Definition

Post-traumatic growth is a psychological transformation that follows a stressful encounter. It is a way of finding the purpose of pain and looking beyond the struggle.

Richard G. Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun coined the term ‘post-traumatic growth’ in the mid-90s at the University of Carolina. According to them, people who undergo post-traumatic growth flourish in life with a greater appreciation and more resilience. They define PTG as a positive psychological change in the wake of struggling with highly challenging life circumstances (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 2004).

PTG involves life-altering and favorable psychological changes that can potentially change the way we perceive the world. It comes with a new understanding of life, relationships, money, success, and health.

Post-traumatic growth goes beyond acknowledgment or acceptance. It entwines personal strength and self-dependence; and while the pain may still be hurting, we get a new way of redirecting the pain to something useful for us.

The positive transformation of PTG reflects in one or more of the following five areas:

- Embracing new opportunities – both at the personal and the professional fronts.

- Improved personal relationships and increased pleasure derived from being around people we love.

- A heightened sense of gratitude toward life altogether.

- Greater spiritual connection.

- Increased emotional strength and resilience.

Not everyone who undergoes trauma experience post-traumatic growth. Individual responses and emotional perception of the damaged guide the way he adapts and learns from it in the long run.

Some studies have shown that almost 90% of trauma victims have reported to experience at least one aspect of post-traumatic growth after the stressful encounter (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 1990). In a nutshell, Post-Traumatic Growth is a positive indicator of recovery and healthy coping.

While the grief may still be there, post-traumatic growth allows us to look forward in life instead of being stuck in the past.

A Look at the Psychology and Theory

Post-traumatic growth is also called by other names such as – finding benefits, stress-related growth, thriving, adversarial growth, and positive psychological changes (Affleck & Tennen, 1996; O’Leary, Alday, & Ickovics, 1998; Park, Cohen, & Murch, 1996; Yalom & Lieberman, 1991).

There are diverse theoretical orientations of the concept of PTG, provided by researchers of different schools of Psychology. What is common in all the literature reviews related to PTG is the fact that it is an outcome of a struggle and involves futuristic coping mechanisms (Schaefer & Moos, 1992, 1998; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995, 2004).

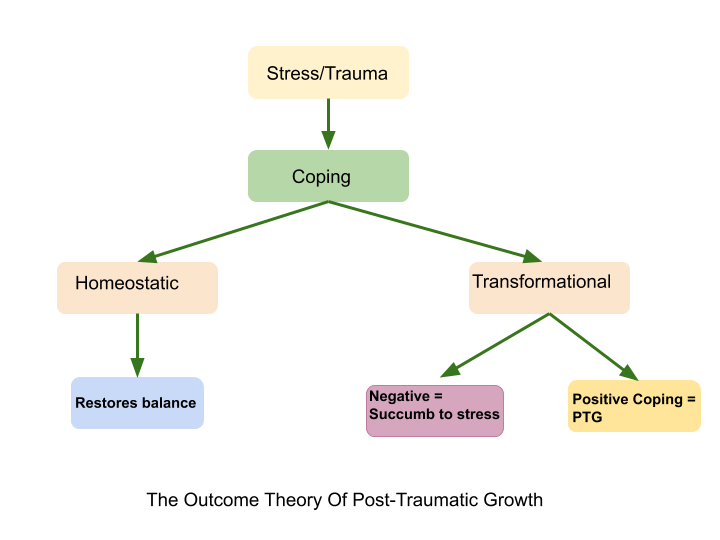

The Outcome Theory

General models of psychological and mindset shift view change as a consequence of attempts to cope with life and stress (Janoff-Bulman, 1992).

Some theorists state that stress is not necessarily a negative aspect for us. Stress does have an inevitable component of transformation and personal growth (Aldwin, 2009). The outcome theory of Post-Traumatic Growth is built around this concept.

The theory asserts that PTG is the outcome of coping and reflects human strength and resilience. There are two types of coping, as the Outcome Theory states – Homeostatic Coping and Transformational Coping.

- Homeostatic coping is restorative. It returns us to our healthy functioning without guaranteeing personal development.

- Transformational coping, on the other hand, comes with cognitive changes within our persona. When transformational coping is negative, one is likely to succumb to stress and revert to depression and worry. However, if the transformational coping is positive, it invites a surge of survival instincts, a higher level of recovery, and increased inner strength to sail through the adversity (Schaefer & Moos, 1992).

The outcome theory suggests that the nature of coping we engage in decides what outcome we invite to our lives. The basic idea of the Outcome Theory is to explain why PTG is a consequence and not a cause, and how we can consciously embrace the positive transformation to thrive (O’Leary & Ickovics, 1995).

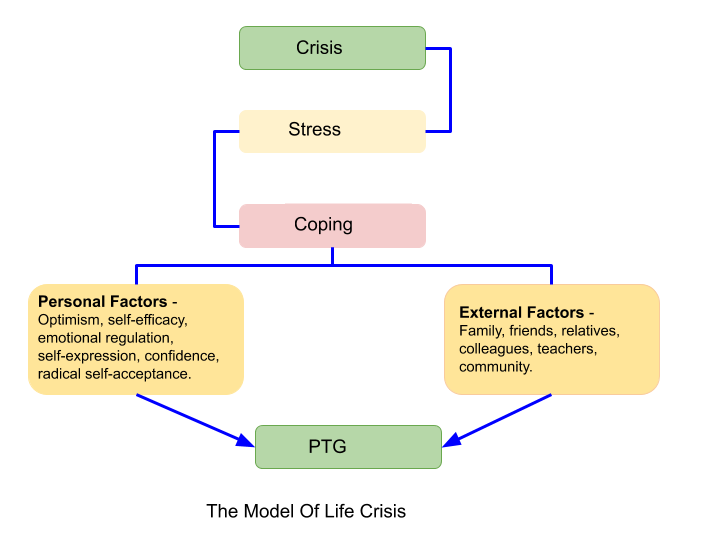

The Model of Life Crisis and Personal Growth

The Model of Life Crisis and Growth outlines the importance of environmental and personal factors in bringing about the positive outcome of stress (Schaefer and Moos, 1992).

The theory suggests that environmental factors, to a large extent, determine the aftermath of worry and hazards. A person who has a caring circle is more likely to undergo positive PTG than someone who has demoralizing people around.

Proponents of this theory emphasize the fact that what happens to us is often beyond our control, but who we choose to be with during times of stress, may make all the difference in life.

Personal factors that contribute to positive PTG include:

- Self-efficacy

- Emotional regulation

- Self-expression

- Confidence

- Radical self-acceptance

- Health

- Past experience

The environmental factors desirable for PTG are:

- Family

- Personal relationships

- Friends

- Colleagues

- Supervisors

- Teachers or guides

- Community

- Financial resources

- Neighborhood

Together with the personal, external, and situational factors, an individual collects the strength to look at the bigger picture and bounce back after setbacks.

Research and Studies

Studies have found a positive correlation between PTG, psychological development, and physical wellbeing (Park & Helgeson, 2006).

Some investigations on German prisoners, refugees, accident victims, and terror attack survivors suggested some significant positive relationship between post-traumatic growth and PTSD (Maercker, 1998).

Few studies could establish a strong association between PTG and depression (Curbow, Somerfield, Baker, Wingard, & Legro, 1993), however, in many instances, subjects undergoing positive transformation did report depressive symptoms.

Some extensive research and studies on cancer survivors and war victims showed significant PTG and a surprisingly high level of optimism and self-motivation, with increased feelings of gratitude and self-appreciation (Znoj, 1999).

Furthermore, studies also indicated that those who underwent prominent PTG did not suffer from grief and anxiety for over 12 months post-transformation (Frazier, Conlon, & Glaser, 2001).

A study on individuals suffering personal losses found that when facilitators showed them how to use the pain for self-enhancement rather than self-destruction, the signs of depression visibly reduced (Davis et al., 1998).

The effect of PTG reflected in their daily mood and regular activities, and they reported greater insight into life in general (Tennen, Affleck, Urrows, Higgins, and Mendola, 1992).

A Brief History of PTG Thinking

The phenomenon of growth after trauma has been observed for about as long as humans have been suffering – which is to say, always. The theme can be found woven throughout our religious texts, mythologies, and stories handed down through generations, philosophical musings, literature throughout the ages, and in our more modern mediums of television and film.

PTG was formally recognized as a psychological theory in the mid-1990s when researchers Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun officially proposed the theory (Collier, 2016).

Over the last two decades, psychologists have engaged in many studies of this theory and discovered some valuable truths about PTG, including:

- PTG tends to be stable over time.

- People high in openness to experience and extroversion are more likely to experience PTG.

- Slightly more women experience PTG than men.

- Those in late adolescence and early adulthood are more open to PTG than children and older adults.

- The ability to grow after trauma may be linked to gene RGS2, which is associated with fear-related disorders (including PTSD, panic disorder, and anxiety).

- Psychological stress and dysfunction predict PTG, but optimism and future orientation do as well (Collier, 2016).

While these findings are encouraging, it never hurts to view new theories with a dash of doubt. A study from 2009 found that, although many participants who had experienced a traumatic event reported growth related to the trauma, this growth was not always verified by actual improvements in functioning (Frazier et al., 2009). PTG is certainly possible, but it may not be as widespread and easily achieved as some proponents of the theory believe.

Regardless, the theory has provided hope to countless people and spawned multiple resources and methods of facilitating healing and growth among those who need it most.

A Look at the Work of Tedeschi and Calhoun

Richard G. Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun were the proponents of the concept of Post-Traumatic Growth (1995). Their ‘functional-descriptive model of PTG‘ described the growth as an outcome of active coping and indicated how it could change our worldviews and life goals instantly.

Tedeschi and Calhoun viewed PTG as a ‘visionary change.’ According to their revised model of PTG, the emotional distress that follows a painful encounter can be more empowering than self-debilitating.

Their studies indicated how PTG calls for higher-order thoughts, beliefs, and actions, and initiates a reduction of emotional distress.

Their theory suggested the following key characteristics of PTG that causes psychological change:

- PTG comes with multidimensional changes in the belief system, life goals, and self-identity.

- It is constructive and mindful as it helps us stay grounded and focus on what is happening now rather than dwelling in the past.

- It is value-oriented as it changes the way we look at life altogether.

- It is goal-oriented as it helps us stay focused on our aims and higher goals.

- It calls for self-improvement as we become regardful and start valuing what we have.

- It changes our reasoning and judgmental qualities.

- PTG is tied in with self-dependence and self-healing. The deep understanding that one derives during the post-traumatic transformation makes him self-reliant and solution-focused.

Calhoun and Tedeschi suggested that two factors contribute to affective dysregulation that follows a failure or personal loss”

- Proximal factors – including internal correlates such as thought, judgment, and emotional meaning.

- Distal factors – including factors external to the self, such as people we live with, environmental setting, etc.

PTG addresses the proximal factors with higher priority than the distal factors. The theorists suggested and proved that when individuals learn to tame their inner critics, the scope for PTG is much higher.

Besides, strong internal capacities also aid in regulating the distal factors and optimize their impact on our lives. To help people apply and incorporate this theory in life, Tedeschi and Calhoun developed an inventory that researchers and individuals could use for evaluating post-traumatic growth.

More on the inventory is discussed in the upcoming sections.

5 Examples of Post-Traumatic Growth

Post-traumatic growth comes in different ways – sometimes as selfless help to others or occasionally as genuine self-understanding and acceptance.

Here are some examples of how post-traumatic growth can look in real life:

- An ideal illustration of post-traumatic growth is parents who have lost their child to cancer, raising money for different cancer organizations or charities.

- Survivors of terrorist attacks often become friendlier and more accepting of others. Much of their behavioral change owes to the trauma they had faced.

- Another bright instance of post-trauma growth is war victims and soldiers who return safely from battle gain a broader perspective of life.

- People who lose someone dear at a tender age are much more grateful and appreciative for what they have than others of their age. For example, a child who has lost his mother knows the value of motherly affection and would likely be more emotionally mature than other children of her age.

- Couples who remarry after losing their first spouse often develop a deeper and more transparent relationship. The earlier trauma they had faced in the past drives them to value the present and improve the quality of the interpersonal relationships they have now.

No matter how PTG shows up or which aspect of life they impact, the positive shift of energy that occurs in turning the negative into something good changes our identity as a whole.

PTG and Positive Psychology

Although PTG was initially introduced as a psychological theory (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995), it engaged in a myriad of positive psychology models and interventions in the last two decades (Collier, 2016).

There are a few reasons why researchers feel post-traumatic growth and positive psychology complements each other:

- PTG (Post-Traumatic Growth) involves a stable and permanent shift of mindset, that is capable of ensuring our wellbeing in the long-run.

- PTG commensurates with positive psychology in the ways it holds for all personality types and traits. Whether one shows introversion or openness, or neurotic characters, everyone is capable of undergoing the positive shift that comes with PTG.

Besides psychological stress and trauma, certain positive traits predict post-traumatic growth, for example, optimism, futuristic thoughts, and resilience.

When Martin Seligman started the positive psychology movement in the early 90s, he devoted a significant portion of his research to the positive personal development that follows a traumatic encounter.

His analysis indicated that post-traumatic growth in adult individuals marked a higher level of physical and psychological functioning in them. Also, they showed greater resilience and solution-focused coping during future stressful encounters they experienced.

Seligman suggested that PTG is not merely a by-product of trauma; it acts as a catalyst to bring about the cognitive restructuring that helps us grow as better human beings (Fredrickson, 2004).

PTG acts as a shield against mental breakdown. It reduces the impact of grief and stress in the future. Studies show that individuals who transformed PTG had more life satisfaction and a better quality of life (QoL).

Interventions such as SMART (Stress Management and Resiliency Training) or MBSR (Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction), showed that survivors who underwent PTG were more self-focused than other subjects (Sood, Prasad, Schroeder, & Varkey, 2011).

Another form of resilience training is the Realizing Resilience Masterclass© which will equip you with invaluable tools and the six most important pillars of resilience. It is a practitioner’s ultimate shortcut to presenting Mastering Resilience classes and for coaches to provide training.

Post Traumatic Growth and Resilience

We often speak of post-traumatic growth and emotional resilience in the same line, but in psychology, they are two entirely independent constructs.

Resilience is a personal quality to bounce back from stress and sorrow – some of us are inherently more resilient than others.

Whereas, PTG is an enlightened mental state that comes after one is exposed to trauma. Although resilience can help make the most of the PTG, we should not equate one with the other. A resilient person may not undergo PTG after encountering stress; on the other hand, a person who has experienced PTG may not have been resilient before the trauma.

It takes time and immense struggle to truly change after a trauma. When a less resilient person suddenly faces a setback, he may become baffled and overwhelmed by the stress. However, this state of confusion and the endless struggle may lead him towards post-traumatic growth.

Therefore, it is too early to deduce a direct association between resilience and post-traumatic growth. While we cannot deny the pieces of evidence that show how PTG brings resilience, the existing research indicating their independence should also be noted (Lepore & Revenson, 2006).

| PTG and Resilience – A Brief Comparative Analysis | |

|---|---|

| Similarities between Post-traumatic growth and Resilience | |

|

|

| Differences | |

| Post-traumatic growth | Resilience |

| PTG is often a consequence of trauma. | Resilience is usually a part of personal disposition. |

| PTG is capable of changing our personality as a whole. | Resilience does not call for a change. |

| People who underwent PTG have definitely been exposed to stress at some point in their lives. | A resilient person may not necessarily have been exposed to trauma or suffering. |

What Common Forms of Therapy are used for PTG?

Here is a list of some of the standard therapeutic strategies that welcome PTG and self-development.

1. Reality Therapy

Reality therapy aims to provide a clear insight to clients about where they are and where they can go from here. It entwines life satisfaction, goal-orientation, and induces objectivity into individuals under stress (Glasser, 1965).

2. Accelerated Resolution Therapy

Accelerated Resolution Therapy or ART combines parts of cognitive therapy and introduce solution-focused emotional control to minimize the effect of traumatic life events.

Including exercises such as EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), voluntary memory replacement, guided imagery, and hypnotherapy, ART effectively works for individuals with PTSD, depression, and emotional problems (GoodTherapy, 2018a).

3. Body-Mind Psychotherapy

Body-Mind Psychotherapy combines elements of the psychosomatic and cognitive approach to mental wellbeing. It uses components of CBT, homeostasis, and motor development. By using techniques of mindfulness, relaxation, and sensory awareness, this form of psychotherapy help trauma survivors to regain self-awareness and get back in touch with themselves (GoodTherapy, 2018b).

A Look at Post-Traumatic Growth Syndrome

Some researchers argue that PTG is a ‘motivated positive illusion’ that develops as a defense mechanism or an escape from the real emotions (Lommen, Engelhard, van de Schoot, & van den Hout, 2014).

Studies indicated that people often manifest PTG symptoms during times of distress because they refuse to believe that something terrible has happened to them.

For example, research on Iraq soldiers revealed that many of them showed signs of PTG, but reportedly manifested worsening of symptoms in the long-run. The real transformation that follows PTG usually ensures emotional improvement rather than deterioration.

Psychologists called this post-traumatic growth syndrome, where a sudden, short-lived positive emotional flow occurs after a trauma, and which ultimately leads to distress rather than contentment.

Studies show that 30-70% of the adult population who undergo trauma show this change of mindset and overcome the sudden setback that the trauma brings (Joseph & Butler, 2010). A fundamental feature of PTG is conscious focus and attention on the recovery process.

However, as an initial reaction to stress, we often tend to perceive ourselves as potentially weak. The onset of PTG marks a shift of perspective from ‘I am the victim’ to ‘I am a survivor.’

A Look at the Possible Symptoms of PTG

- A significant improvement in existing interpersonal relationships, including friends, family, and work associates.

- Enhanced self-perception and self-acceptance. PTG shields us against self-harming thoughts and actions.

- A marked alteration in the philosophy and meaning of life, with more resilience to future stressors.

- An echoing sense of thriving and heightened self-motivation. Individuals who undergo post-traumatic growth realize the importance of self-dependence and learn to live in their terms (Meichenbaum, 2006).

- Greater self-expression and social connectivity.

- An optimistic view of life with new goals, motives, and the desire for achievement.

- A rise in the urge for moving on – trauma survivors who change through PTG are open about their problems and focus more on their life ahead. They successfully unstuck themselves from the past and looked forward.

- A visible increase in relatability. Studies by Tedeschi and Calhoun showed that individuals who go through personal development after trauma are more empathetic and can relate to others’ struggles better than they did before.

The process of healing that follows PTG is rarely the same for everyone. Although the indicators above are accurate in most cases, PTG can also manifest itself with symptoms that are exceptional and highly subjective.

At its most basic form, PTG is marked by five indicators that Tedeschi and Calhoun mentioned in their Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI):

- Appreciation

- Relationships

- New possibilities and opportunities

- Personal strength

- Spiritual enhancement

We will discuss these factors in detail in the upcoming section on PTGI below.

What is the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory?

Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) developed the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) to assess post-trauma growth and self-improvement a person undergoes. A 21-item scale built on the five-factor model of Tedeschi, this inventory is one of the most valid and reliable resources for evaluating personal growth that follows a stressful encounter.

The statements included in the inventory are related to the following five factors:

Factor I – Relating to Others

Factor II – New Possibilities

Factor III – Personal Strength

Factor IV – Spiritual Enhancement

Factor V – Appreciation

Each of the 21 items falls under one of the five factors and are scored accordingly. A summation of the scores indicates the level of post-traumatic growth.

The advantage of this scale is that the categorization of scores according to the five factors are suggestive of which area of self-development is predominant in us and which area might be a little behind.

For example, a high total score implies that the person has undergone a positive transformation. But a closer look at the scores of each section would provide a more in-depth insight into what has changed significantly and what aspects of the self may still need some improvement.

The PTGI was initially developed to measure favorable outcomes of a stressful life event. But with time, it became more popular as a test that provides direction to the participants about their future actions and suggests scope for self-improvement (Cann, Calhoun, Tedeschi, & Solomon, 2010).

Where Can I Find the Scale?

Participants indicate their scores on a 6-point scale where:

- 0 implies – I did not experience this as a result of my crisis.

- 1 implies – I experienced this change to a very small degree as a result of my crisis.

- 2 implies – I experienced this change to a small degree as a result of my crisis.

- 3 implies – I experienced this change to a moderate degree as a result of my crisis.

- 4 implies – I experienced this change to a great degree as a result of my crisis.

- 5 implies – I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my crisis.

Below is an overview of the test items along with the categorization of the five factors.

| Factor | Item Numbers |

|---|---|

| 1 – Relating to others | 6, 8, 9,15, 16, 20, 21 |

| 2 – New Possibilities | 3, 7, 11, 14, 17 |

| 3 – Personal Strength | 4, 10, 12, 19 |

| 4 – Spiritual Enhancement | 5 |

| 5 – Appreciation | 1, 2, 13 |

The Post Traumatic Growth Inventory

PTGI is widely available online. Below is an illustration of the form:

| Statements | Scoring | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|

|

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

|

| | | | | | | | | | | | |

Common Criticisms of PTG

Despite the undeniable motivational boost that PTG brings with it, some researchers raised quite a few questions regarding the reliability of this concept as a whole. Some of the noteworthy grounds of criticism of the PTG theory includes:

Positive illusion

Significant studies over the years raised questions about whether PTG truly reflects wellbeing. Some evidence indicates that the subjective feeling of contentment that individuals experienced in PTG is perceived happiness rather than real joy.

Scientists argued that it is practically impossible to compare levels of wellbeing prior and post-trauma, as PTG only assesses the level of satisfaction after a stressful encounter. It has limited resources to analyze how well the person had been doing before the trauma (Bellizzi et al., 2010; Ruini, Vescovelli, & Albieri, 2013).

Correlation with distress

Some researchers argued that PTG and depression could coexist in an individual. A study on cancer survivors showed that many of them who underwent PTG did not show a significant change in their Quality of Life.

Besides, they also showed signs of grief, which indicated a weak association between PTG and distress (Bussell & Naus, 2010; Schroevers & Teo, 2008).

Demographic barriers

Initially, PTGI was administered on a large sample of the adult female population. Later, the assessment, along with the theory behind it faced criticism on whether the results can be validated for the male population and whether PTG can be held for children and young people.

Unfortunately, we have very little evidence that counters this criticism (Fobair et al., 2002; Oz, Dil, Inci, & Kamisli, 2012).

5 Recommended TED Talks and YouTube Videos

Take some time out, relax and watch these powerful talks and videos.

1. TED Talk On Post Traumatic Growth by Harry Brown

Dr. Harry Brown is a psychologist and a teacher who has a significant contribution in popularizing the psychological change that follows trauma. His TED Talk on PTG sheds light on the concept of uncertainty and how we can use it as an anecdote to acceptance and emotional catharsis.

2. Post-traumatic Growth After Childhood Cancer

PTG in children is rarely discussed. Dr. Lamia Barakat, an expert practitioner at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has put forth some of her groundbreaking studies on how young cancer survivors can beat the trauma and bounce back to life.

3. Post Traumatic Growth by Vanessa Van Edwards

Vanessa Van Edwards is a famous American author, speaker, and language trainer. Her video on PTG and the positive mindset shift associated with it is relatable to all and explains the real-life implications of it.

4. What is Post-Traumatic Growth by Sonja Lyubomirsky

This short video by Sonja Lyubomirsky, a renowned psychologist, professor, and author of the bestseller ‘The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want,’ explains the basics of PTG and provides a pathway for beginning to explore it. With fundamental explanations backed by cutting-edge scientific evidence, this video is an eye-opener for all aspects of PTG.

5. Richard Tedeschi on Posttraumatic Growth: Basic Concepts and Strategies for Facilitation

Richard Tedeschi’s contribution to the field of PTG is unmatchable, and this video is a brief compilation of his most valuable findings on the subject. It is an excellent resource for professionals or self-help seekers of all ages.

4 Books on the Topic

Another excellent way to delve into the amazing capabilities of humans to overcome trauma, look into any one of the following books.

1. Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications – Richard G. Tedeschi, Jane Shakespeare-Finch, Kanako Taku, and Lawrence Calhoun

The authors and proponents of the PTG theory and PTGI, have presented a collection of their cross-cultural studies that validate the usefulness of PTG in enriching our wellbeing.

Find the book on Amazon.

2. Posttraumatic Growth: Positive Changes in the Aftermath of Crisis (Personality and Clinical Psychology) – Richard G. Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun

It includes practical methods for applying the theory in real life and suggests ways for clinicians and therapists to use PTG tools for promoting insight and enhanced meaning in life.

Find the book on Amazon.

3. Upside: The New Science of Post-Traumatic Growth – Jim Rendon

Find the book on Amazon.

4. Posttraumatic Growth Workbook – Richard Tedeschi and Bret Moore

Activities covering essential areas such as self-awareness, emotional regulation, inner strength, and capabilities, this guide can be the ultimate self-help manual for overcoming trauma effectively by ourselves.

Find the book on Amazon.

10 Quotes

Your trauma is not your fault, but your healing is your responsibility.

I am better off healed than I ever was unbroken.

Beth Moore

Healing comes from gathering wisdom from past actions and letting go of the pain that the education cost you.

Caroline Myss

Thoughts could leave deeper scars than almost anything else.

Keep going. Difficult roads often lead to beautiful destinations.

Take all the time you need to heal emotionally. Heal at your own pace, step by step, day by day.

There is always a day for you but till then you have to wait trying.

Anish Tamilvanan

It is only in your thriving that you have anything to offer to anyone.

Esther Hicks

Take life as you find it, but don’t leave it that way.

Difficulties are meant to rouse, not discourage. The human spirit is to grow strong by conflict.

William E. Channing

A Take-Home Message

Our understanding of trauma and its impact on the mind and body is still the tip of an iceberg. There is a lot more in this field that researchers are still working on. No matter what, the way we connect to ourselves after encountering a disaster is undoubtedly more meaningful than our usual ‘me-times.’

PTG lets us accept the inevitable changes. It provides us with the power to direct the struggle in a way that would keep us moving forward. And as the saying goes:

There are far better things ahead than any we leave behind.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Grief Exercises [PDF] for free.

- Affleck, G., & Tennen, H. (1996). Construing benefits from adversity: Adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings. Journal of Personality, 64(4), 899-922.

- Aldwin, C. M. (2009). Stress, coping, and development: An integrative perspective (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Bellizzi, K. M., Smith, A. W., Reeve, B. B., Alfano, C. M., Bernstein, L., Meeske, K., … & Ballard-Barbash, R. R. (2010). Posttraumatic growth and health-related quality of life in a racially diverse cohort of breast cancer survivors. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(4), 615-626.

- Bussell, V. A., & Naus, M. J. (2010). A longitudinal investigation of coping and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 28(1), 61-78.

- Calhoun, L. G., & Tedeschi, R. G. (1990). Positive aspects of critical life problems: Recollections of grief. Omega-Journal of Death and Dying, 20(4), 265-272.

- Calhoun, L. G. & Tedeschi, R. G. (2014). Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research & practice. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., & Solomon, D. T. (2010). Posttraumatic growth and depreciation as independent experiences and predictors of well-being. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 15(3), 151-166.

- Collier, L. (2016). Growth after trauma: Why are some people more resilient than others – and can it be taught American Psychological Association, 47(10), 48.

- Curbow, B., Somerfield, M. R., Baker, F., Wingard, J. R., & Legro, M. W. (1993). Personal changes, dispositional optimism, and psychological adjustment to bone marrow transplantation. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16(5), 423-443.

- Davis, C. G., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Larson, J. (1998). Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: Two construals of meaning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), 561-574.

- Fobair, P., Koopman, C., Dimiceli, S., O’Hanlan, K., Butler, L. D., Classen, C., … & Spiegel, D. (2002). Psychosocial intervention for lesbians with primary breast cancer. Psycho‐Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 11(5), 427-438.

- Frazier, P., Conlon, A., & Glaser, T. (2001). Positive and negative life changes following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 1048-1055.

- Frazier, P., Tennen, H., Gavian, M., Park, C., Tomich, P., & Tashiro, T. (2009). Does self-reported posttraumatic growth reflect genuine positive change? Psychological Science, 20(7), 912-919.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367-1377.

- Glasser, W. (1965). Reality therapy. In J. K. Zeig (Ed.), The evolution of psychotherapy: The second conference (p. 270-283). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel.

- GoodTherapy. (2018a). Accelerated Resolution Therapy (ART). Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/accelerated-resolution-therapy

- GoodTherapy. (2018b). Body-Mind Psychotherapy. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/body-mind-psychotherapy

- Janoff-Bulman, R. (2010). Shattered assumptions. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- Joseph, S., & Butler, L. D. (2010). Positive changes following adversity. PTSD Research Quarterly, 21(3), 1–7.

- Lepore, S. J., & Revenson, T. A. (2006). Resilience and posttraumatic growth: Recovery, resistance, and reconfiguration. In L. G. Calhoun & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research & practice (p. 24–46). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Lommen, M. J., Engelhard, I. M., van de Schoot, R., & van den Hout, M. A. (2014). Anger: cause or consequence of posttraumatic stress? A prospective study of Dutch soldiers. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(2), 200-207.

- Maercker, A. (1998). Posttraumatische Belastungsstörungen: Psychologie der Extrembelastungsfolgen bei Opfern politischer Gewalt [Posttraumatic stress disorder: Psychology of extreme distress in victims of political violence]. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst.

- O’Leary, V. E., Alday, C. S., & Ickovics, J. R. (1998). Models of life change and posttraumatic growth. In R. G. Tedeschi, C. L. Park & L. G. Calhoun (Eds.), Posttraumatic Growth: Positive changes in the aftermath of crisis (pp. 133-156). Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

- O’Leary, V. E., & Ickovics, J. R. (1995). Resilience and thriving in response to challenge: an opportunity for a paradigm shift in women’s health. Women’s Health (Hillsdale, NJ), 1(2), 121-142.

- Oz, F., Dil, S., Inci, F., & Kamisli, S. (2012). Evaluation of group counseling for women with breast cancer in Turkey. Cancer Nursing, 35(4), E27-E34.

- Park, C. L., Cohen, L. H., & Murch, R. L. (1996). Assessment and prediction of stress‐related growth. Journal of Personality, 64(1), 71-105.

- Park, C. L., & Helgeson, V. S. (2006). Introduction to the special section: growth following highly stressful life events: Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 791-796.

- Ruini, C., Vescovelli, F., & Albieri, E. (2013). Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer survivors: New insights into its relationships with well-being and distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 20(3), 383-391.

- Schaefer, J. A., & Moos, R. H. (1992). Life crises and personal growth. In B. N. Carpenter (Ed.), Personal coping: Theory, research, and application (p. 149–170). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Schaefer, J. A., & Moos, R. H. (1998). The context for posttraumatic growth: Life crises, individual and social resources, and coping. In R. G. Tedeschi, C. L. Park & L. G. Calhoun (Eds.), Posttraumatic growth: Positive changes in the aftermath of crisis (pp. 99-125). Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

- Schroevers, M. J., & Teo, I. (2008). The report of posttraumatic growth in Malaysian cancer patients: Relationships with psychological distress and coping strategies. Psycho‐oncology, 17(12), 1239-1246.

- Sood, A., Prasad, K., Schroeder, D., & Varkey, P. (2011). Stress management and resilience training among Department of Medicine faculty: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(8), 858-861.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1995). Trauma and transformation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455-471.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1-18.

- Tennen, H., Affleck, G., Urrows, S., Higgins, P., & Mendola, R. (1992). Perceiving control, construing benefits, and daily processes in rheumatoid arthritis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 24(2), 186-203.

- Yalom, I. D., & Lieberman, M. A. (1991). Bereavement and heightened existential awareness. Psychiatry, 54(4), 334-345.

- Znoj, H. J. (1999, August 20-24). European and American perspectives on posttraumatic growth: A model of personal growth. Life challenges and transformation following loss and physical handicap. Paper presented at the 107th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED435886.pdf

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (41)

- Coaching & Application (49)

- Compassion (27)

- Counseling (46)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (16)

- Grief & Bereavement (19)

- Happiness & SWB (35)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (21)

- Mindfulness (42)

- Motivation & Goals (42)

- Optimism & Mindset (33)

- Positive CBT (24)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (41)

- Positive Emotions (28)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (38)

- Relationships (31)

- Resilience & Coping (33)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Software & Apps (23)

- Strengths & Virtues (28)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (27)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (30)

- Types of Therapy (53)

What our readers think

I am self-publishing a book about recovery and healing from trauma related to 17 years of lived experience in foster care. This article is extremely helpful in introducing readers to the concept of posttraumatic growth (PTG), and making the distinction between PTG and resilience. I am not a researcher, just a trauma survivor and writer. What permissions are required to reference and reproduce the PTG Inventory in my book? Thank you for your review and reply.

Hi there,

As far as I know, there are no specific permissions required to reference PTG in other works. I think it is sufficient to cite the work by Tedeschi & Calhoun by using this reference:

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1-18.

The PTGI is free to use for research purposes without permission from the authors, but I am unsure what the exact procedure would be to use it in the book. Usually referencing should be enough, but to be sure I would suggest reaching out to the authors when it comes to reproducing the PTGI in your book.

Best of luck with publishing your book!

-Caroline | Community Manager

We are trying to obtain the permission to reuse the PTGI among refugee women living in Jordan for a Master of Public Health student. The work will be published and we seek permission to use the tool and translate it into Arabic using a panel of experts in the field.

How can we obtain the permission to reuse the PTGI?

Hi Khalid,

This scale is free to use and translate for research purposes without permission from the authors.

Hope this helps!

– Nicole | Community Manager

My therapist recently mentioned PTG and after some research am pleasantly surprised. I have hope of a long anticipated fuller life. Thanks for sharing your perceptions.

Henry deTourdonnet

Hello Madhuleena,

Who developed The outcome theory of Post-Traumatic Growth that is mentioned above?

Thank you

Karen

Hi Karen,

I believe this perspective was introduced by O’Leary and Ickovics (1995).

– Nicole | Community Manager

Hello Nicole,

thank you for your reply, its been so helpful!