The 3 Best Questionnaires for Measuring Values

Our values fuel our actions, emotions, and behavior.

Our values fuel our actions, emotions, and behavior.

They are a crucial aspect of significant branches of studies, including sociology, philosophy, education, and psychology.

Values are tied in with ethics and morals; they guide our judgment and prepare us to choose actions according to their consequences.

The human value system serves self-exploration, self-enhancement, and self-recognition. Values are “freely chosen, verbally constructed consequences of ongoing, dynamic, evolving patterns of activity, which establish predominant reinforcers for actions that are intrinsic in engagement in the valued behavioral pattern itself” (Wilson & DuFrene, 2009, p. 66).

Psychologists believe in the transformative power of values. Studies have shown that ethics and values can change our inner world and alter the way we perceive and react to stimuli. For example, a person who has regard for honesty will genuinely reflect the same actions. That person would be less likely to engage in behaviors such as lying, stealing, cheating, or using any unfair means to accomplish set goals.

Whether personal, professional, social, or life-oriented, values make room for knowledge, wisdom, and heightened self-realization. They are unique and individualized. We all choose different combinations of values in life, and these choices shape our actions and life decisions. Clarifying values is a great way to prioritize our life goals and understand what we truly desire to become.

In this article, we will discuss some of the most popular and standardized measures for evaluating our personal and core values. We will know what value assessments are, why we need them, and where we can find them. The value-based inventories and questionnaires mentioned in this piece will let you tune in to your inner standards and determine what means the most to you.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our 3 Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free. These creative, science-based exercises will help you learn more about your values, motivations and goals and will give you the tools to inspire a sense of meaning in the lives of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

- The Valued Living Questionnaire (VLQ)

- What Does the VLQ Measure Exactly?

- A Look at the VLQ Validity

- Where Can You Find the Valued Living Questionnaire?

- The (Schwartz) Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ)

- What Versions Are There?

- What Does the PVQ Measure Exactly?

- A Look at the PVQ Validity

- Where Can You Find the Portrait Values Questionnaire?

- The Personal Values Assessment (PVA)

- What Does the PVA Measure Exactly?

- A Look at the Validity of the PVA

- Where Can You Find the PVA Questionnaire? (+ PDF)

- A Take-Home Message

- References

The Valued Living Questionnaire (VLQ)

Values develop from personal experiences, observational learning, and environmental influences. Regardless of how we cultivate them, moral values are crucially important to our inner peace and balance. Going against them, no matter why, brings in a lot of tension and can be overwhelming for us.

The principle theory of value revolves around the concept of a ‘value system’ – a set of deep-rooted standards that form the foundation of our actions and life choices. Our values are built on ten domains of living, and this is what the Valued Living Questionnaire attempts to evaluate.

The ten areas include:

- Family

- Marriage and intimate relationships

- Parenting

- Friendship and interpersonal relationships

- Professional life

- Academic life

- Leisure and recreation

- Spirituality

- Citizenship

- Self-care

Some scientists working on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy initially created the Valued Living Questionnaire (VLQ). They found that valued living was a vital component that works behind the successful implementation of radical self-acceptance and commitment to positive change (Hayes, 2004; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999).

The VLQ is a simple self-report measure that emphasizes on the values that are unique to us. It also explores how valued living across the ten domains of life have influenced our actions over the past few days. The responses are scored on a 10-point Likert Scale that indicates how significant the particular value is to us.

With high test-retest reliability and consistent validity, the VLQ is a great way to get started on estimating the specific standards that define our living (Wilson, Sandoz, Kitchens, & Roberts, 2010).

What Does the VLQ Measure Exactly?

It is associated with other core processes such as mindful living, acceptance, mental balance, reduced distress, and overall adjustment (Wilson & Murrell, 2004).

The Valued Living Questionnaire systematically assesses the extent to which individuals regard their values and incorporates them into daily actions. That values influence our everyday activities was initially mentioned in the Acceptance and Commitment Theory but became the foundation of the valued living test.

The VLQ assesses three main things:

- Identifying the domains of valued living that we think are most important to us.

- Suggesting how the domains influenced our actions over the past week.

- Evaluating the degree to which our actions are consistent with our values (VLQ; Wilson et al., 2010).

A Look at the VLQ Validity

Some studies on the effectiveness of the VLQ across varied settings showed that there is a significant positive correlation between what values mean to us and how much we act according to them (Floyd & Widaman, 1995).

Consistent validity was relatively high for the VLQ assessment, indicating that the results are more or less constant across populations of different backgrounds (Wilson et al., 2010).

Construct validity of the Valued Living Questionnaire, and some other standard assessments (such as the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire) were evaluated in research on a large sample of undergraduate university students.

The results indicated significant validity of the scores and found greater consistency among the VLQ results of the participants.

Where Can You Find the Valued Living Questionnaire?

Although the VLQ originally evolved as part of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, it is now a widely accepted measure of estimating the domains of life values that govern our actions. The scale has two sets of questions – one that evaluates our meaning of the values and one that estimates how the values have impacted our activities over the past week.

It is a self-scoreable form and is quick to administer. Respondents record their scores on a 10-point Likert Scale where ‘1’ means ‘not at all important,’ and ’10’ implies ‘extremely important.’

In the second part of the form, the responses range from ‘1’ – ‘totally inconsistent with my values’ to ’10’ – ‘totally consistent with my values’ in the second part of the test.

You can find the test online. Below is a brief illustration of the assessment form:

Valued Living Questionnaire (VLQ)

Below are statements on some areas of life that most people value. Rate them on a scale of 1-10, where ‘1’ implies ‘not at all important’ and ‘10’ means ‘extremely important.’ Respond to each item according to your sense of value; there are no right or wrong answers here.

| Statements | Score |

|---|---|

| Family (excluding marriage and parenting) | | |

| Marriage and other intimate personal relationships | | |

| Parenting | | |

| Friends/social life | | |

| Professional life | | |

| Academic life | | |

| Recreation or leisure | | |

| Spirituality | | |

| Community life | | |

| Physical self-care | | |

Below are statements on some areas of life that most people value. Respond to each item according to how ‘you feel’ you have followed the values over the past seven days. Rate the statements on a scale of 1-10, where ‘1’ implies ‘not at all consistent with my values,’ and ’10’ means ‘completely consistent with my values.’

| Statements | Score |

|---|---|

| Family (excluding marriage and parenting) | | |

| Marriage and other intimate personal relationships | | |

| Parenting | | |

| Friends/social life | | |

| Professional life | | |

| Academic life | | |

| Recreation or leisure | | |

| Spirituality | | |

| Community life | | |

| Physical self-care | | |

The (Schwartz) Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ)

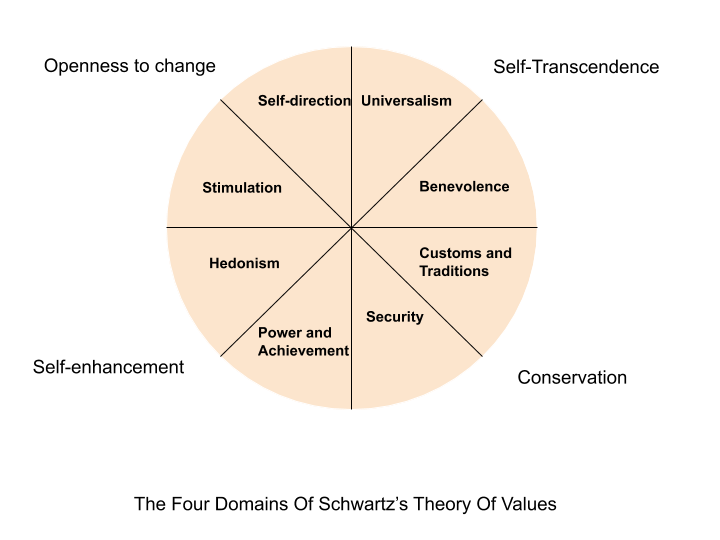

The Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) is based on Schwartz’s theory of values. Schwartz and his colleagues in 2001 explained that ten fundamental individual values influence human actions at any point.

These are:

- Self-directional values – that define our goals and ambitions in life.

- Stimulative values – that provide the energy and vigor to move ahead for accomplishing the aspirations.

- Hedonistic values – that operate on the pleasure principle and instant need gratification.

- Achievement values – that define personal success and competence.

- Power values – that come with societal norms, control, and personal resources.

- Security values – including personal safety, harmony, interpersonal relationships, and self-control.

- Conformity values – that operate through agreeableness to societal norms and standards.

- Traditional values – involving respect, community support, commitment, and acceptance of customs and culture.

- Benevolent values – that is tied in with preservation and enhancement of the welfare of self and others close to us.

- Universal values – that encompass appreciation, tolerance, and general acceptance of the nature of things around us.

The ten values in this scale are organized into four domains:

- A self-directional domain that operates on openness and flexibility to change.

- A universal value domain that is influenced by transcendence.

- Traditional values domain that is motivated by the laws of conservation.

- Power value domain that is governed by self-enhancement.

The assessment comes with several relatable statements about how we feel about ourselves and others. Respondents rate each statement according to what they think is most appropriate for them. The results explain which of the four domains play a predominant role in the individual’s life and also suggests how to make the most of it.

What Versions Are There?

The Portrait Values Questionnaire comes in four different versions:

- A long-form version (PVQ-40), containing a list of 40 portrait values from which respondents choose the ones most important to them.

- A short-form version or PVQ-21 containing 21 portrait values from which individuals choose the ones that influence them the most.

- A male version that contains some portrait values and standards unique to the adult male population.

- A female version containing universal and personal values, unique to the adult female population (Schwartz, 1992; 1994).

The values in each variation are obtained by assessing their relatability, and how often individuals use them on a day-to-day basis. The respondents compare themselves to each portrait value and identify how much it resonates with them. The response pattern follows a 6-point Likert Scale ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 6 (totally like me).

What Does the PVQ Measure Exactly?

The long-form and short-form versions of the PVQ evaluate values across the ten dimensions of Schwartz’s theory (Steinmetz, Schmidt, Tina-Booh, Wieczorek, & Schwartz, 2009).

It also justifies the four-factor model that Schwartz had mentioned and helps respondents to compare themselves under different life situations.

PVQ provides a strong base for self-evaluation, which is why it is suitable for use with children, young adults, and older individuals across different demographic settings (Davidov, Schmidt, & Schwartz, 2008).

Many scientists have recognized the PVQ scale to be a valid alternative to the Schwartz Value Survey (SVS) which is a 56-item measure of 11 motivational value types, due to its independent nature and universal acceptability.

Studies show that the reduction in the number of items for the PVQ short form does not interfere with the validity or reliability of the test. It is a universal measure of personal value systems and carefully evaluates the underlying causes of our actions and perceptions (Schwartz et al., 2001).

A Look at the PVQ Validity

A two-nation study investigated the validity and reliability of the Portrait Value Questionnaire (PVQ-21).

Although there were some debates regarding the multi-factor approach of the test, no significant studies could disprove its efficiency and practical applications (Krosnick & Presser, 2010). The PVQ underwent several cross-cultural examinations to evaluate its validity across different populations.

A study on adult consumers of more than 20 European countries found that the multi-group structure of the test was valid for respondents of different age, sex, and stages of life.

Significant studies and analyses of the PVQ have proved that the ten values and the four domains of Schwartz’s theory are consistent and remain invariant. By far, PVQ is one of the universally accepted valid value assessment scales.

Where Can You Find the Portrait Values Questionnaire?

The Portrait Value Questionnaire is a relatable and straightforward assessment that we can take by ourselves, and you can access a PDF copy of the test for free.

Below is a brief description of the short-form PVQ test.

The Portrait Value Questionnaire (PVQ-21) Female Version

Below are some statements that describe a person. Read them carefully and respond to how each statement resonates with you as a person. Rate your responses on a scale of 1-6, where ‘1’ means ‘very much like me,’ and ‘6’ implies ‘not at all like me.’

| Statements | Score |

|---|---|

| 1. Thinking up new ideas and being creative is important to me. | | |

| 2. It is important for me to be rich and have a lot of money. | | |

| 3. I believe that every person in the world should be treated equally. | | |

| 4. It is important for me to show my abilities. I want other people to admire what I do. | | |

| 5. It is important for me to live in a safe and secure surrounding. | | |

| 6. I love surprises and always want to try something new. | | |

| 7. I believe that I should obey rules even when no one is around. | | |

| 8. It is important for me to stay humble and modest. | | |

| 9. I believe in listening to people who are different from me and try to understand them. | | |

| 10. Having a good time is important to me. I like to ‘spoil’ myself at times. | | |

| 11. I prefer to make my own decisions and do what feels right to me. | | |

| 12. I like helping people around me. | | |

| 13. Being successful is important to me. | | |

| 14. It is important for me to ensure that the government is taking care of my safety concerns. | | |

| 15. I want to take up new adventures and want to live an exciting life. | | |

| 16. It is important for me to behave properly at all times and not do anything that people consider wrong. | | |

| 17. It is important for me to earn respect from others. | | |

| 18. Being loyal to my friends is a priority in my life. | | |

| 19. I try to follow my traditional values and customs that my family and society have endowed on me. | | |

| 20. I strongly believe that we should care about nature. | | |

| 21. It is important for me to do things that give me pleasure. | | |

The Personal Values Assessment (PVA)

Values are broadly classified into three sub-types:

- Personal Values – that define who we are, what we want, and why we think the way we do.

- Social Values – that govern our social connections and interpersonal bond with others.

- Universal Values – that influence spiritual thought, cultural standards, and overall acceptance of life experiences.

The Personal Values Assessment (PVA) is a short and straightforward measure of determining our core values and personal belief system.

The theoretical orientation of the test suggests that self-image, self-acceptance, and our life goals are all aligned to our core personal values.

The PVA is a quick survey that takes only a few minutes to complete but provides a detailed estimate of the causal factors behind our internal drives and decision-making abilities.

The test allows us to understand what we think is important to us and commensurate those ideals with our day-to-day activities. Also, the order in which we choose our responses determines the importance of personal values in our lives.

What Does the PVA Measure Exactly?

What we say, what we hold inside, and how we evaluate experiences are all parts of what values we follow. The PVA aims to assess the underlying causes of our actions.

The test lets us realize what our core values are and why we act or react in accordance to them. The form is simple and objective and provides a linear evaluation of how aligned we are to our internal values and judgment at present.

Furthermore, the test also suggests ways to restore mental balance and reduce internal conflicts by reflecting our values on our actions.

Although the PVA is a self-assessment, respondents do not evaluate the results themselves. A detailed result with explanation follows successful completion of the form, which helps understand how connected we are to our internal standards.

A Look at the Validity of the PVA

Studies on the relationship between values, professional interests, personal choices, and personality disposition have indicated that the PVA is a significant predictor of the overall value system of an individual.

Validity and efficacy of the test also reflected in the hierarchical studies of the different factors used in the PVQ model.

Overall, the Personal Values Questionnaire provides a substantial base work for ruling one’s standards of right and wrong, and evaluate how one incorporates values at the personal, professional, and social fronts of life (Leuty & Hansen, 2011).

Where Can You Find the PVA Questionnaire? (+ PDF)

The PVA is a quick assessment that you can use as a self-help tool at any point. You can take the full online test which would take about five-ten minutes to complete, and below is a short version of the form for better understanding.

Personal Details

| Select any ten values from the list below that you think are most important for you: |

|---|

| Accountability, Achievement, Adaptability, Ambition, Balance, Being liked, Being the best, Caring, Caution, Clarity, Coaching, Commitment, Community Life, Compassion, Competence, Conflict management, Continuous learning, Control, Courage, Creativity, Dialogue, Ease with uncertainty, Efficiency, Positivity, Entrepreneurial nature, Environmental awareness, Ethics, Excellence, Fairness, Family, Finances, Forgiveness, Friendship, Future generations, Generosity, Health, Humility, Humor, Independence, Initiative, Integrity, Independence, Job security, Leadership, Listening skills, Openness, Patience, Perseverance, Personal contentment, Personal growth, Personal Growth, Professional Growth, Power, Resilience, Self-discipline, Trust, Wisdom. |

A Take-Home Message

Living by our values is comfortable and comes to us naturally. Through value assessments like the ones mentioned in this article, we can help ourselves grow and be one step closer to enhanced self-understanding.

The purpose of these evaluations is not to spotlight where we are falling short or make us self-critical. Instead, these evaluations remind us of our purpose of living and drive us closer to what truly matters to us.

Values let us know what is right for us. When we share and internalize values, they allow us to know ourselves better and guide us to choose what is best for us.

To quote the words of Sri Satya Sai, a popular spiritual leader, and mentor:

Values should predominate thoughts; as human life has no meaning without them.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our 3 Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free.

- Davidov, E., Schmidt, P., & Schwartz, S. H. (2008). Bringing values back in: The adequacy of the European Social Survey to measure values in 20 countries. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(3), 420-445.

- Floyd, F. J., & Widaman, K. F. (1995). Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 286-299.

- Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and the new behavior therapies: Mindfulness, acceptance and relationship. In S. C. Hayes, V. M. Follette, & M. Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive behavioral tradition (pp. 1–29). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1-25.

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Krosnick, J. A., & Presser, S. (2010). Question and questionnaire design. In P. Marsden & J. D. Wright (Eds.), Handbook of survey research (Vol. 2, pp. 263–314). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Leuty, M. E., & Hansen, J. I. C. (2011). Evidence of construct validity for work values. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 379-390.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). New York: Academic Press.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Beyond individualism/collectivism: New cultural dimensions of values. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, C. Kagitcibasi, S. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications (pp. 85–119). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S., Harris, M., & Owens, V. (2001). Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human values with a different method of measurement. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 32(5), 519-542.

- Steinmetz, H., Schmidt, P., Tina-Booh, A., Wieczorek, S., & Schwartz, S. H. (2009). Testing measurement invariance using multigroup CFA: Differences between educational groups in human values measurement. Quality & Quantity, 43(4), 599-616.

- Wilson, K. G., & Dufrene, T. (2009). Mindfulness for two: An acceptance and commitment therapy approach to mindfulness in psychotherapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

- Wilson, K. G., & Murrell, A. R. (2004). Values work in acceptance and commitment therapy. In S. C. Hayes, V. M. Follette, & M. M. Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition (pp. 120-151). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Wilson, K. G., Sandoz, E. K., Kitchens, J., & Roberts, M. (2010). The Valued Living Questionnaire: Defining and measuring valued action within a behavioral framework. The Psychological Record, 60(2), 249-272.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (41)

- Coaching & Application (49)

- Compassion (27)

- Counseling (46)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (16)

- Grief & Bereavement (19)

- Happiness & SWB (35)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (21)

- Mindfulness (42)

- Motivation & Goals (42)

- Optimism & Mindset (33)

- Positive CBT (24)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (41)

- Positive Emotions (28)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (38)

- Relationships (31)

- Resilience & Coping (33)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Software & Apps (23)

- Strengths & Virtues (28)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (27)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (30)

- Types of Therapy (53)

What our readers think

very helpful

This post basically make you view yourself

Gives you a social standing without bias

This was very useful and I wish people could read it for their understanding

I like how they made me give my self a self examination. So I could better understand who I am

I really liked these questions and they made me think alot about self awareness.